What bugs me about "radical uncertainty" boosters is that they seem to me to downplay how important information acquisition costs are and that one we realize there's a chance (i.e. - a probability) of

something that we can't attach a probability to or even a name to, normal decision making starts to pierce through at least little.

But it's clear that information acquisition costs are not the whole story - that there is uncertainty in addition to risk.

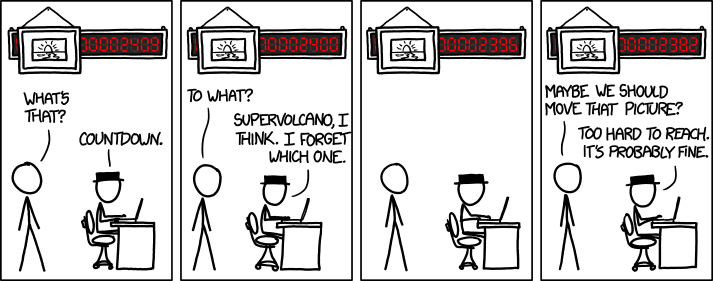

We laugh at this comic because we know how crazy it is to reduce dealing with the reality of radical uncertainty to a cost-benefit analysis of information acquisition costs.

>>there's a chance (i.e. - a probability) of something that we can't attach a probability to or even a name to<<

ReplyDeleteIsn't that self-contradictory?

The fact that we write papers about "radical uncertainty" and can conceive of the reality and significance of these events suggests to me it's not self-contradictory, but I could be wrong.

DeleteObviously we are limited in how we can deal with this.

I can say with confidence that I know there are unknown unknowns out there... what is 'unknown' is the details of that unknown unknown, right? I am not hopeless in dealing with this, but I am limited. I can stay liquid or keep a stockpile of a random assortment of stuff. I can dedicate resources to speculative excursions, etc.

This is what I mean by the normal way we deal with risk "piercing through" (despite the fact that a lot of people like to treat it as completely different).

Essentially what I'm saying is that unknown unknowns - by virtue of the very fact that we have made this category - are actually known. They are "known unknown unknowns". And if people want to kick the can further I can just walk up and kick it back (known unknown unknown unknowns).

There is some extent to which we know these things are an issue - that's why we're talking about it after all! This is all really just a matter of degree, more than I think a lot of people are willing to admit.

It is useful to kick the can once: to differentiate between "known unknowns" and "unknown unknowns". In other words, it is useful to note that not all unknowns are the same.

That we know there are unknown unknowns doesn't mean we actually know what these unknown unknowns are. Similarly, just because we know there are limits to our knowledge this doesn't mean we necessarily know everything outside our limits. I agree thought that we employ means of reducing the unknown unknown (e.g. reading the newspaper), so there must be some degree of probability that can be applied.

DeleteWhile you do differentiate between known unknowns and unknown unknowns Daniel Kuehn, you seem to forget that uncertainty/ambiguity is actually best mathematically captured as an interval. The problem is not the unknown unknown so much as dealing with partial and conflicting information...

ReplyDeletehttp://www.amazon.com/review/R1SVTG4B3QOJBH

This comment has been removed by the author.

ReplyDeleteIt does seem paradoxical to say that we can *know* there are unknown unknowns (in the future), despite the fact that minimal self-awareness reveals that the unfolding of a human life is in large part a series of surprises (unknown unknowns).

ReplyDeleteHow can we connect our *knowledge* of our past radical *ignorance* of unknown unknowns to a "knowledge," or at least a suspicion, that unknown unknowns will plague us in the future? I think we have to have a theory of human or societal ontology that would explain why, in the past, we have been so radically ignorant, rather than (as I have sometimes done) leaving the explanation for unknown unknowns at the level of "we are not omniscient." I.e., I think we need a theory about something on the order of the constitution of the human mind that explains why, in the past, it has proved unable to predict human behavior in modern social contexts. And this theory would have to be plausible enough that we could be confident that its premises will persist into the future, such that we could know that we will continue to be radically ignorant of human behavior ex ante.

I'll develop my theory in my forthcoming book, *No Exit: The Problem with Social Democracy.* But in brief, the theory is that each of us is exposed to a different stream of information that produces different interpretations of the significance and implications of new information, leading to different actions in response to that information.

So we can't forecast very well how others (or even we ourselves) will react to some new development (say, a new product or a new public policy) in the future.

I hate to defend Buchanan, because I think public-choice theory is a priori, largely incorrect political science. However, in the passage you've discussed about preferences, Buchanan seems to be saying that we can be surprised by our own preferences at the moment they are revealed. I am saying that, a fortiori, we are even more likely to be surprised at the preferences/behaviors of others.

Can we prepare for unknown unknowns? We can try, and sometimes we may succeed. In trying, I agree that one denies (or tries to defy) radical ignorance by proposing, in effect, that one knows at least the general form that the unknown unknown will take, or by proposing that one has thought of everything (in effect, no matter how humble and fallibilistic one's attitude). However, while such denials/defiances are necessary to human action--i.e., the conviction that we know what we are doing is inescapable--that doesn't mean that the conviction is true, as we see from the many failed business ventures and investments that always litter the capitalist landscape.