But the self-referentialism isn't the real problem here - the problem is the foundationalism. Perhaps the phrase "knowledge about knowledge" changed the emphasis and that's my fault.

What foundation do we have for true knowledge? None that I can think of. So how do we really have knowledge about knowledge? You can substitute in "how do we really have knowledge about reality?" or "how do we really have knowledge about truth?" to realize that the real problem here is foundationalism. As I've said many times on here before, I'm no philosopher. Evan can at least pass as one, so if he finds that too cavalier he can clarify.

Bob Murphy jumps in on the self-referentialism theme: "Daniel, get this, there are apparently idiots out there writing books on grammar. I mean, how could you read a book about proper grammar, if you didn't already know it? The book would be gibberish to you, right?"

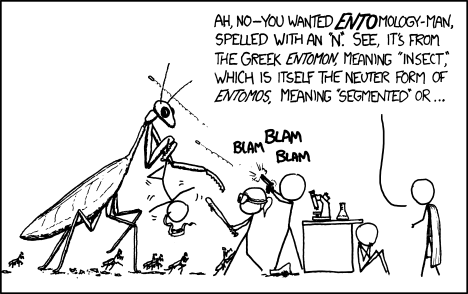

But this analogy doesn't work and it really highlights my point. We make up grammar (or some sort of natural selection process does the job for us). "Because that's just the way it is" is a perfectly valid answer to the question "why must my subject and my verb agree?". If the question is "why is 'the subject and verb must agree' the way it is in this language?", you could probably add some kind of historical explanation on top of that, but that's not grammar anymore - that's history and perhaps a little etymology depending on exactly what your question is (not to be confused with entomology):

It's apt that Bob brings up grammar, in fact, and that I am making the point that grammar is OK to proceed in a way that these discussions of "truth", "knowledge", and "reality" are not. After all - that is exactly the point that Wittgenstein makes, is it not (seriously... is it not? That's not rhetorical. I'm no philosopher.) We can proceed in talking about grammar and language. We cannot proceed in talking about these "deeper" (read "mostly vacuous") questions.

Also in the thread, I said to Evan "we all have implicit assumptions that we work off of that one could call epistemological and metaphysical assumptions. I'm not sure you can say that means we're doing epistemology or metaphysics", and Mattheus writes in response to that: "But these assumptions need to be an explicit part of your science. Lay them out on the table so we can challenge and refine them."

No they don't.

Gene already told Mattheus that as a historical matter they don't need to be an explicit part of your science, and he agreed. Now, if you're interested in arguing about these things - if you're interested in doing philosophy in other words - then by all means enjoy arguing about these things. But I hope you can appreciate the scientists lack of interest in making these assumptions explicit or arguing about them when you haven't even given a reason why that argument would have any consequence at all for understanding the phenomenon that we are trying to explain.

Finally, there was some discussion about methods of knowing things or strategies for getting knowledge. Again, I'm no philosopher but that sounds like methodology and that seems like a worthwhile thing to talk about to me. Talking about what "knowledge is" or what "truth is" seems very different from that. I'm sure there's stuff that epistemologists talk about that's valuable from a methodological perspective. A lot of what Mattheus is interested in might be worth talking about from the viewpoint of methodology.

Wikipedia gives us three bullet points to sum this up in discussing epistemology:

- What is knowledge?

- How is knowledge acquired?

- To what extent is it possible for a given subject or entity to be known?

My assertion is that the first and the third are pretty silly things to argue or care about (but I ascribe to subjective utility theory - by all means if you enjoy arguing about it, then argue about it). I will grant that the second bullet point might lead to discussions that have value insofar as they shed light on methodology. But my point is that the thing that really makes this epistemology - the "knowledge" part - is the least important element of the second bullet. Indeed, to the extent that the person who pursues the second bullet preoccupies herself with whether what is being acquired is actually "knowledge", pursuits of the second bullet probably become less useful.

My comment is too large and cluttered for a response. I'll write something on ET in response.

ReplyDeleteI await it eagerly :)

DeleteI guess I would add that when we get into the methods of acquiring knowledge they naturally overlap 1) and 3)

ReplyDelete