What else does a guy need to distract him from finishing his essay by 5 pm today?

I'll be listening to Prof. Vegh lecture on "fiscal policy over the business cycle" at the annual Frank Tamagna Lecture here are AU. I imagine it's going to be related to this work on the very strange tendency towards pro-cyclical fiscal policy and the role of good institutions in breaking out of the pro-cyclicality trap.

Tuesday, April 30, 2013

Three quick STEM labor market links

Doing a lot of writing today but I didn't want these to fall through the cracks:

1. The Atlantic picks up our EPI report. Good coverage, and what was especially cool was the short discussion at the end of the article about the author's change of opinion on the issue.

2. I wanted to bring people's attention to the blog Chemblogger, which covers the labor market for chemists. Lots of podcasts on the blog - you may be seeing me on there soon :). The coverage of our report is here.

3. The House Committee on Science, Space, and Technology is trying to get language in NSF legislation with the intent of limiting funding for research. I don't know how likely this is to pass or if in practice it would be easy for the NSF to navigate around it, but the intent is depressing enough. (HT - Dr. J).

1. The Atlantic picks up our EPI report. Good coverage, and what was especially cool was the short discussion at the end of the article about the author's change of opinion on the issue.

2. I wanted to bring people's attention to the blog Chemblogger, which covers the labor market for chemists. Lots of podcasts on the blog - you may be seeing me on there soon :). The coverage of our report is here.

3. The House Committee on Science, Space, and Technology is trying to get language in NSF legislation with the intent of limiting funding for research. I don't know how likely this is to pass or if in practice it would be easy for the NSF to navigate around it, but the intent is depressing enough. (HT - Dr. J).

Monday, April 29, 2013

Citizen Hearing on Disclosure - for those of you interested in this sort of thing

UFOs are a tough subject for a scientifically minded person to be interested in. If you're a Carl Sagan you can speculate with ease because hey, you're Carl Sagan. The problem for most people is that there's a lot of crazy stuff out there, a lot of doctored events, and a lot that we simply can't verify.

And the unverifiability is part of the point, of course. I'm sure everyone has heard the refrain "that's what the 'U' stands for!". Some people think they have a better grasp of what's behind that 'U' than others.

One thing that's probably fairly certain is that the government has good information on UFOs no matter what they are. If they are nothing substantive, than the government is no better off than we are pretty much by definition (there's not much to know). If UFOs are extraterrestrial or extradimensional or simply a black budget project (or some combination of the above) the government almost certainly knows more than we do. That is the point of the Citizen Hearing on Disclosure, which starts today. Like similar earlier events at the National Press Club, the nice thing about this citizen hearing is that it tries very hard to separate out the level-headed witnesses and researchers from the tin-foil crowd. Emphasis in these things is always on mass-sightings and the observations made by the military, by pilots, and by astronauts. I can't speak for this event - it hasn't happened yet! - but usually efforts like this are extremely careful not to be speculative.

My view is that it's a subject worthy of taking an interest in but unworthy of firm conclusions at this point. I take a casual/amateurish interest in it myself. A few things seem clear:

If you agree, you might be interested in checking in on the Citizen Hearing this week.

And the unverifiability is part of the point, of course. I'm sure everyone has heard the refrain "that's what the 'U' stands for!". Some people think they have a better grasp of what's behind that 'U' than others.

One thing that's probably fairly certain is that the government has good information on UFOs no matter what they are. If they are nothing substantive, than the government is no better off than we are pretty much by definition (there's not much to know). If UFOs are extraterrestrial or extradimensional or simply a black budget project (or some combination of the above) the government almost certainly knows more than we do. That is the point of the Citizen Hearing on Disclosure, which starts today. Like similar earlier events at the National Press Club, the nice thing about this citizen hearing is that it tries very hard to separate out the level-headed witnesses and researchers from the tin-foil crowd. Emphasis in these things is always on mass-sightings and the observations made by the military, by pilots, and by astronauts. I can't speak for this event - it hasn't happened yet! - but usually efforts like this are extremely careful not to be speculative.

My view is that it's a subject worthy of taking an interest in but unworthy of firm conclusions at this point. I take a casual/amateurish interest in it myself. A few things seem clear:

1. There is a very high probability that the galaxy and the universe is full of life.None of this is clear cut, but to me it adds up to something that a rational person can be reasonably intrigued by.

2. We are at the very cusp of our own space-faring age and relatively rudimentary in our technology (we burn old dinosaur bones and peat moss for God's sake - that's just a step above burning dung).

3. There are a lot of UFO sightings (1,210 reported [not necessarily occurring] in 2013 to date by one record keeper), of course of varying quality. Of course there are a lot of reported abductions too but that's a touchier area. Let's stick with sightings.

4. Governments around the world are clearly keeping files on these events - it is something they are interested in for whatever reason, and

5. There are a few very high profile events - particularly Roswell, New Mexico - with a considerably richer eye-witness record.

If you agree, you might be interested in checking in on the Citizen Hearing this week.

What lies ahead...

- Finish gender macro paper on gender disparities in science and engineering as a constraint on growth

- Ben's wedding

- Macro final

- Studystudystudystudy

- Info-metrics two day class

- Studystudystudystudy

- Macro theory comp

- Prepare some of this year's papers for submission

- [??????]

- Paint/prepare the nursery

- Labor Economics and Info-metrics seminar

- Attend the birth of my child

- Try to divide my time between labor, info-metrics, kid, and Sloan work without going insane

- Ben's wedding

- Macro final

- Studystudystudystudy

- Info-metrics two day class

- Studystudystudystudy

- Macro theory comp

- Prepare some of this year's papers for submission

- [??????]

- Paint/prepare the nursery

- Labor Economics and Info-metrics seminar

- Attend the birth of my child

- Try to divide my time between labor, info-metrics, kid, and Sloan work without going insane

Estimating potential output - a potential idea

The last two posts have had me thinking about potential output. I had an idea that I'd like to think I may do something with eventually, but I probably won't. This semester in my microeconometrics seminar a lot of people interested in economic development have lead the discussion and presented their own papers, and many have used stochastic frontier analysis (SFA), an efficiency estimation technique common in the development literature. SFA essentially has two error terms - one is a classical mean-zero error term and the other is the "technical inefficiency component" that is the departure from the technical frontier. Obviously assumptions around the error structure are going to influence the resulting estimate of inefficiency.

My understanding of potential GDP estimates is that they use things like medium- to long-term growth rates, and some standard macro relations (Okun's law for example) with capacity utilization and unemployment statistics to estimate economic potential.

It seems to me another way you could do this is to take state-level data from the BEA (goes back to the 1960s only, but that's OK) and do an SFA estimate of potential output. It would be akin to the capacity utilization approach conceptually, but you'd actually be getting the production function parameters from the data rather than by (what I assume is) assumption.

Any thoughts on the idea?

My understanding of potential GDP estimates is that they use things like medium- to long-term growth rates, and some standard macro relations (Okun's law for example) with capacity utilization and unemployment statistics to estimate economic potential.

It seems to me another way you could do this is to take state-level data from the BEA (goes back to the 1960s only, but that's OK) and do an SFA estimate of potential output. It would be akin to the capacity utilization approach conceptually, but you'd actually be getting the production function parameters from the data rather than by (what I assume is) assumption.

Any thoughts on the idea?

OK Bob Murphy needs to explain what I'm missing about rates vs. levels

Bob Murphy writes:

Can someone please explain what Bob Murphy is doing here? It makes no sense to me.

It seems like we should be talking about rates of change, not levels. And it seems to me we should be comparing to a counter-factual of some sort (the output gap), which is precisely what he criticizes as "loading the deck". I don't see how identifying a counterfactual is loading the deck - that's the only way to do good science.

If Bob wants to cite or write up a literature on a persuasive alternative counterfactual that's one thing.

But don't imply that the extant literature is cheating. It's essential to making any scientific claim and it appears to be the most persuasive argument.

This is just like David Henderson's accusation of "proof by assumption". Suddenly going with the extant literature becomes tantamount to cheating - "loading the deck". Why? It seems like a weighty accusation to accuse another analysis of cheating. It seems like you have to have a better case than this if you're going to do that.

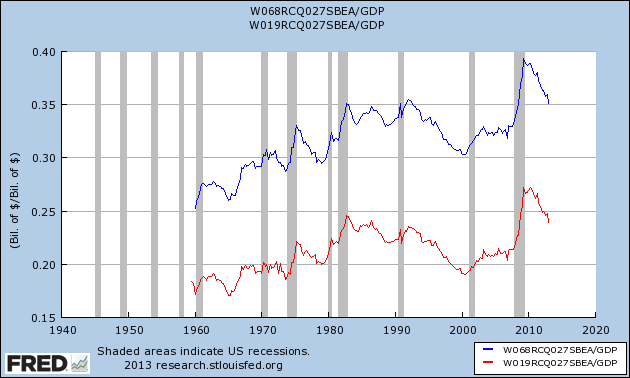

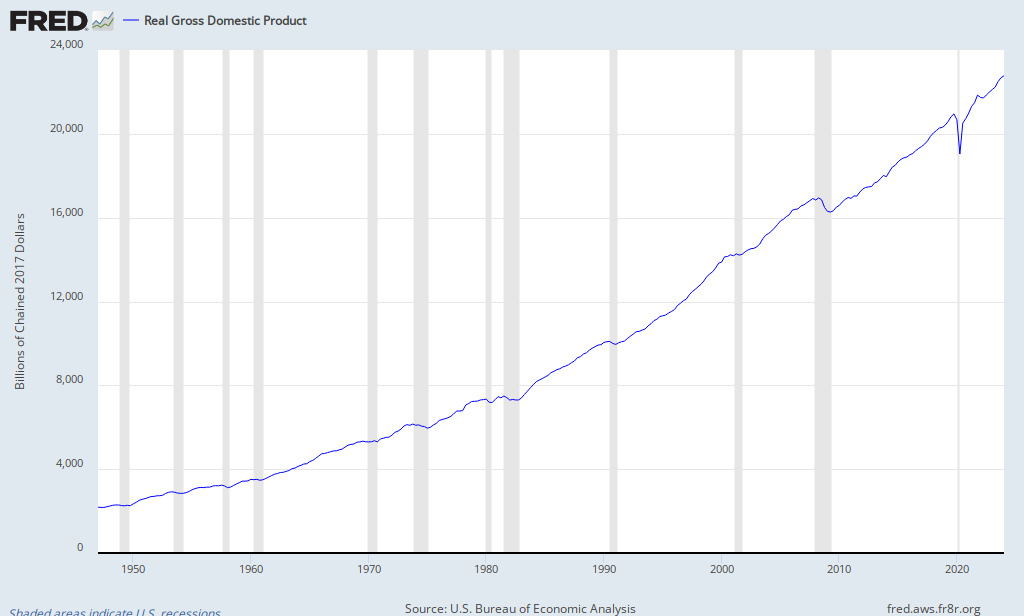

Let’s see what happens if we take (a) total government and (b) federal government expenditures, and divide by actual GDP, not “potential” GDP. We find this:

So granted, despite a relentless decline in total and federal expenditures per dollar of GDP (and a lot of the stimulus increase just filling the hole that the states were digging), government spending per dollar of GDP is the highest it's ever been. Agreed. But if you're using that metric then how can you conclude that "the economy right now is arguably worse than it was during the Great Depression", as Bob does? If you are assessing policy based on levels of government spending and levels of GDP, shouldn't you be measuring performance based on levels too? That also seems to be the highest it's ever been:Huh, how ’bout that? According to this metric, government spending (whether total or just federal) is still higher than at just about any point in the last 50 years, save for the crisis period itself and a few little blips. Couple that with the fact that the economy right now is arguably worse than it was during the Great Depression–both DeLong and Krugman tell us this is so–and it’s a good prima facie case that massive government spending hurts the economy. That should make sense, because it lines up perfectly with commonsense “micro” thinking.

Can someone please explain what Bob Murphy is doing here? It makes no sense to me.

It seems like we should be talking about rates of change, not levels. And it seems to me we should be comparing to a counter-factual of some sort (the output gap), which is precisely what he criticizes as "loading the deck". I don't see how identifying a counterfactual is loading the deck - that's the only way to do good science.

If Bob wants to cite or write up a literature on a persuasive alternative counterfactual that's one thing.

But don't imply that the extant literature is cheating. It's essential to making any scientific claim and it appears to be the most persuasive argument.

This is just like David Henderson's accusation of "proof by assumption". Suddenly going with the extant literature becomes tantamount to cheating - "loading the deck". Why? It seems like a weighty accusation to accuse another analysis of cheating. It seems like you have to have a better case than this if you're going to do that.

The only thing missing from this "major, nationwide economic experiment" is a control group (which is half the experiment, right?)

Yesterday there was a lot of blog talk about Mike Konczal's article on the "major, nationwide economic experiment" testing monetary and fiscal policy - the term that he used for the fiscal austerity and monetary expansion we've been having since last fall.

I didn't weigh in at the time for the reason laid out in the title: it's really too early to say anything much less have this expansive claim about "experiments" that makes no sense. I thought Krugman's post on Konczal's article was pretty good at laying out the argument but only suggesting that "the results aren't looking good for the monetarists". I'll take "aren't looking good" over "nationwide economic experiment" - it claims far less. And of course I suspect both Krugman and Konczal are ultimately right, but you can't claim experimental validation at this point.

We're going to need lots of retrospective studies on this many years from now when all the data are in and we can have several thoughtful years grinding through it rather than putting something together for a Washington Post deadline. These studies are probably going to take multiplier estimates, apply them to the policy variables, and determine what contributions monetary and fiscal policy likely made to the recovery (the approach of Vernon (1994) for the Great Depression) or determination of multipliers from the episode itself (the approach of Romer (1992) or Gordon and Krenn (2010) for the Great Depression), or what is effectively the same thing - estimating the output gap and determining the contributions of policies to the closure of that gap based on the sequence of their appearance (the approach of DeLong and Summers (2009) to the Great Depression).

I think we can make Krugman's suggestive statements about how we think things are falling out (if we care at all about the current unemployed we ought to make these suggestive statements), but I don't think we're ready for the full empirical exercise generating or applying multipliers or counterfactuals just yet.

Which brings me to some accusations of "begging the question". A good example is David Henderson's post on the Konczal article. He writes: "But Irwin's last sentence begs the question. It amounts to saying that the Keynesian model is right about fiscal policy's potence. Certainly Irwin believes that and has a right to believe and write it. But Konzcal can't rely on that if he wants to claim that fiscal policy is more potent than monetary policy. Konzcal is using what I call "proof by assumption."."

This is unfair to Konczal I think and not what we should expect of people in newspaper or even journal articles. You take prior empirical evidence and you use it as the best guide to the world that we have. That's what Konczal and Irwin are doing. They can't relitigate every single scientific question in a newspaper article - they have to take the science as given. It's unfair to say they're committing "proof by assumption" when they do that - what they're committing is "proof by prior evidence". The same is true, for example, of Vernon's (1994) work cited above. He takes prior multiplier estimates and uses them in an analysis of the Great Depression. For a lot of reasons I consider this more accurate than what Romer (1992) does, generating a multiplier from scratch from a fairly crude difference-in-differences estimator. Now could you come along and accuse Vernon (1994) of doing "proof by assumption". What is his only assumption? That we have decades of good empirical work on multipliers and he can rely on that literature. If you don't like the scientific literature of course you might want to tar that as "proof by assumption", but I think that's unfair.

I didn't weigh in at the time for the reason laid out in the title: it's really too early to say anything much less have this expansive claim about "experiments" that makes no sense. I thought Krugman's post on Konczal's article was pretty good at laying out the argument but only suggesting that "the results aren't looking good for the monetarists". I'll take "aren't looking good" over "nationwide economic experiment" - it claims far less. And of course I suspect both Krugman and Konczal are ultimately right, but you can't claim experimental validation at this point.

We're going to need lots of retrospective studies on this many years from now when all the data are in and we can have several thoughtful years grinding through it rather than putting something together for a Washington Post deadline. These studies are probably going to take multiplier estimates, apply them to the policy variables, and determine what contributions monetary and fiscal policy likely made to the recovery (the approach of Vernon (1994) for the Great Depression) or determination of multipliers from the episode itself (the approach of Romer (1992) or Gordon and Krenn (2010) for the Great Depression), or what is effectively the same thing - estimating the output gap and determining the contributions of policies to the closure of that gap based on the sequence of their appearance (the approach of DeLong and Summers (2009) to the Great Depression).

I think we can make Krugman's suggestive statements about how we think things are falling out (if we care at all about the current unemployed we ought to make these suggestive statements), but I don't think we're ready for the full empirical exercise generating or applying multipliers or counterfactuals just yet.

Which brings me to some accusations of "begging the question". A good example is David Henderson's post on the Konczal article. He writes: "But Irwin's last sentence begs the question. It amounts to saying that the Keynesian model is right about fiscal policy's potence. Certainly Irwin believes that and has a right to believe and write it. But Konzcal can't rely on that if he wants to claim that fiscal policy is more potent than monetary policy. Konzcal is using what I call "proof by assumption."."

This is unfair to Konczal I think and not what we should expect of people in newspaper or even journal articles. You take prior empirical evidence and you use it as the best guide to the world that we have. That's what Konczal and Irwin are doing. They can't relitigate every single scientific question in a newspaper article - they have to take the science as given. It's unfair to say they're committing "proof by assumption" when they do that - what they're committing is "proof by prior evidence". The same is true, for example, of Vernon's (1994) work cited above. He takes prior multiplier estimates and uses them in an analysis of the Great Depression. For a lot of reasons I consider this more accurate than what Romer (1992) does, generating a multiplier from scratch from a fairly crude difference-in-differences estimator. Now could you come along and accuse Vernon (1994) of doing "proof by assumption". What is his only assumption? That we have decades of good empirical work on multipliers and he can rely on that literature. If you don't like the scientific literature of course you might want to tar that as "proof by assumption", but I think that's unfair.

Sunday, April 28, 2013

You know that blogger at the New York Times that is a consistently huge proponent of expansionary monetary policy and who gets criticized by opponents for wanting to "run the printing presses"...

...Jonathan Catalan thinks that guy is "making a mistake" for not focusing on monetary policy.

It appears someone has drunk the Scott Sumner Kool-Aid on diagnosing the econ blogosphere. His diagnosis is of Krugman is wrong. Jonathan writes: "If I remember correctly, the reasoning for the change of emphasis to fiscal policy was mainly “political.” Krugman felt that it was more worthwhile to draw attention to fiscal stimulus, because inflation hawks were making it difficult for the Federal Reserve to change its position on the two percent inflation target."

As Jonathan points out and I think Krugman is well aware, there are less political obstacles at the Fed than in Congress. What I remember from the Japan paper and most of his blogging during the crisis is that in a liquidity trap monetary policy works on output through expectations - it cannot work through interest rates. It can't even work through inflation until we reach something approaching full employment again. Expectations are delicate, particularly for a central bank that has cultivated an image of price stabilization so fiscal policy and monetary policy together can work better than just monetary policy in a liquidity trap. The word Krugman always uses is "traction" - fiscal policy helps monetary policy get traction.

I imagine (and I'm only speculating here) that this has much less to do with Jonathan wanting to criticize Krugman and much more to do with Jonathan starting a transformation many Austrians and libertarians have made in the last couple years into realizing that a lot of Austrian macro is bunk and wanting to hitch on to the market monetarist train. John Papola did this virtually overnight and I feel like a lot of internet Austrians followed suit. Ryan Murphy did it a long time ago. I'm guessing something like that may be behind Jonathan's post. That's great - there's a lot to market monetarism. But that wrong way to embrace it is to alienate a huge group of people that agree with you on monetary policy and make public statements that seem to imply there's some kind of big division among economists on what the Fed should do. There's not. If you ask the average non-economist that's fairly up on things and reads the New York Times whether Krugman supports expansionary monetary policy at the Fed they'll say "well of course he does - duh!". If you ask the same person what Scott Sumner thinks, unfortunately he'll probably say "who's Scott Sumner?". I say "unfortunately" because Scott does deserve to be better known. Even among professional economists, a lot of people associate NGDP targeting with Christina Romer, not Sumner, for her 2011 op-ed. Older guys that aren't immersed in the blogosphere and as a result didn't know who Scott Sumner was first got the NGDP targeting message that way.

I don't think anyone has any trouble understanding the Keynesian position that we should be firing on all cylinders. Now the politics of Washington might only ever get us one, but there is no conceivable way that advocating fiscal policy has reduced the prospects of expansionary monetary policy.

It appears someone has drunk the Scott Sumner Kool-Aid on diagnosing the econ blogosphere. His diagnosis is of Krugman is wrong. Jonathan writes: "If I remember correctly, the reasoning for the change of emphasis to fiscal policy was mainly “political.” Krugman felt that it was more worthwhile to draw attention to fiscal stimulus, because inflation hawks were making it difficult for the Federal Reserve to change its position on the two percent inflation target."

As Jonathan points out and I think Krugman is well aware, there are less political obstacles at the Fed than in Congress. What I remember from the Japan paper and most of his blogging during the crisis is that in a liquidity trap monetary policy works on output through expectations - it cannot work through interest rates. It can't even work through inflation until we reach something approaching full employment again. Expectations are delicate, particularly for a central bank that has cultivated an image of price stabilization so fiscal policy and monetary policy together can work better than just monetary policy in a liquidity trap. The word Krugman always uses is "traction" - fiscal policy helps monetary policy get traction.

I imagine (and I'm only speculating here) that this has much less to do with Jonathan wanting to criticize Krugman and much more to do with Jonathan starting a transformation many Austrians and libertarians have made in the last couple years into realizing that a lot of Austrian macro is bunk and wanting to hitch on to the market monetarist train. John Papola did this virtually overnight and I feel like a lot of internet Austrians followed suit. Ryan Murphy did it a long time ago. I'm guessing something like that may be behind Jonathan's post. That's great - there's a lot to market monetarism. But that wrong way to embrace it is to alienate a huge group of people that agree with you on monetary policy and make public statements that seem to imply there's some kind of big division among economists on what the Fed should do. There's not. If you ask the average non-economist that's fairly up on things and reads the New York Times whether Krugman supports expansionary monetary policy at the Fed they'll say "well of course he does - duh!". If you ask the same person what Scott Sumner thinks, unfortunately he'll probably say "who's Scott Sumner?". I say "unfortunately" because Scott does deserve to be better known. Even among professional economists, a lot of people associate NGDP targeting with Christina Romer, not Sumner, for her 2011 op-ed. Older guys that aren't immersed in the blogosphere and as a result didn't know who Scott Sumner was first got the NGDP targeting message that way.

I don't think anyone has any trouble understanding the Keynesian position that we should be firing on all cylinders. Now the politics of Washington might only ever get us one, but there is no conceivable way that advocating fiscal policy has reduced the prospects of expansionary monetary policy.

Saturday, April 27, 2013

Overpaid or underpaid?

I don't know the literature on public vs. private pay and I'm hesitant to say one way or another because the story is complicated. Public sector work is more secure, after all - which means that you don't just need to look at point in time pay differences but consider the question of wages over the life-cycle (high starting wage but slow growth, for example). I don't find the overpaid public worker thesis implausible by any means, but I think it's not a simple story and it probably is pretty different across the skill distribution (high skill workers are likely underpaid, potentially as a result of compensating differentials for a sense of mission in public service).

Anyway - to all those caveats let me add another one. Bryan Caplan discussed this recently and reported:

It's 1973, after all.

If we find a 31 percent wage differential in the federal government does that mean:

1. Government overpays workers because it isn't exposed to market discipline, or

2. Private sector underpays women

I'm guessing it's a mix of both and it's hard to know what to do with this without knowing how it splits out between the two. We often use market prices as benchmarks. There can be good reason for doing that, but I'm not sure I would for an analysis of women in 1973.

Anyway - to all those caveats let me add another one. Bryan Caplan discussed this recently and reported:

"The literature on wage differentials between public and private sector employees spans roughly four decades, originating with Smith's [1976a, 1976b, 1977] seminal series of papers. The core of her analysis is the estimation of conventional human capital earnings functions. For example, in Smith [1976b] she uses 1973 Current Population Survey (CPS) data to estimate for each gender a regression of the logarithm of the wage on various worker characteristics such as years of schooling and race, including a series of dichotomous variables indicating whether each individual worked in the federal, state, or local government sectors (the private sector is the omitted category). For males, she finds wage differentials relative to the private sector of 19 percent in federal government and -4.9 percent in local government. The coefficient on the state government variable is statistically insignificant. The differentials for female workers are 31 percent in federal government, 12 percent in state government, and 3.6 percent in local government."So the exercise and the assessment of differentials is fine (although he goes on to talk about more refinements). We ought to ask whether the research is really finding comparable work in the private sector or not (in a lot of cases, likely not), but what I want to question is how we want to interpret this.

It's 1973, after all.

If we find a 31 percent wage differential in the federal government does that mean:

1. Government overpays workers because it isn't exposed to market discipline, or

2. Private sector underpays women

I'm guessing it's a mix of both and it's hard to know what to do with this without knowing how it splits out between the two. We often use market prices as benchmarks. There can be good reason for doing that, but I'm not sure I would for an analysis of women in 1973.

My favorite commentary on the report so far

John Carney:

A side note on how people talk about this: I've never particularly liked this framing of the problem as "producing more students than there are jobs" for the reasons you might expect an economist not to like that. It's got a "fixed stock of jobs" feel to it, which we know is wrong. My co-author, Hal, has done a lot work in the past on looking at the "STEM pipeline" which is really the fodder for these types of statements and he occasionally uses lines like this (indeed, lines like this are in our report). But I can tell you from having known Hal for a long time and talking with him a lot about these issues that he knows there's not a fixed stock of jobs, he knows how markets work (indeed he shines among sociologists on that one - often sociologists harbor a lot of suspicions and misconceptions). I guess he just says things like that because his different background means he winces at different things than I do. And if that's the case for a sociologist it's even more the case for a journalist.

My only point is, when people word things in a way that you wouldn't word things, don't automatically imbue that with all the significance that you are tempted to. Is Carney's writing here basically right or basically wrong? It's basically right. The difference in phraseology between something I might write and something he might write has to do with differences in our mental models of things rather than our understanding of the underlying point. That's not to say that phrasing can't carry greater significance - it definitely can. Just be careful before assuming it does and ask yourself if they are on the same page as you, just using different words.

"It's high season for economic myth busting.Most of the public probably isn't as deep into the discussion, but I for one don't mind being linked up with the Reinhart/Rogoff discussion!

First, we had the myth of the 90 percent debt-to-GDP ratio busted open. And now one of Washington's other cherished myths—the lack of workers trained in science, technology, engineering, and math (STEM, for short)—has been demolished.

The U.S. has "more than a sufficient supply of workers available to work in STEM occupations," a study released Wednesday by the Economic Policy Institute has found. In fact, we're producing far more STEM graduates than we can place in jobs."

*****

A side note on how people talk about this: I've never particularly liked this framing of the problem as "producing more students than there are jobs" for the reasons you might expect an economist not to like that. It's got a "fixed stock of jobs" feel to it, which we know is wrong. My co-author, Hal, has done a lot work in the past on looking at the "STEM pipeline" which is really the fodder for these types of statements and he occasionally uses lines like this (indeed, lines like this are in our report). But I can tell you from having known Hal for a long time and talking with him a lot about these issues that he knows there's not a fixed stock of jobs, he knows how markets work (indeed he shines among sociologists on that one - often sociologists harbor a lot of suspicions and misconceptions). I guess he just says things like that because his different background means he winces at different things than I do. And if that's the case for a sociologist it's even more the case for a journalist.

My only point is, when people word things in a way that you wouldn't word things, don't automatically imbue that with all the significance that you are tempted to. Is Carney's writing here basically right or basically wrong? It's basically right. The difference in phraseology between something I might write and something he might write has to do with differences in our mental models of things rather than our understanding of the underlying point. That's not to say that phrasing can't carry greater significance - it definitely can. Just be careful before assuming it does and ask yourself if they are on the same page as you, just using different words.

A running list of links to the report (updated)

...for my own records if nothing else.

- Washington Post - good summary, with a focus on the shortage argument

- Slate (Matt Yglesias) - focus on shortage argument - a counter-argument that STEM guestworkers are good anyway but no attempt to explain why we should be uniquely happy to have STEM workers such that we'd give them a special visa

- Philadelphia Inquirer - a more labor protectionist take on the report, with special considerations about New Jersey

- Science Careers (here and here) - by one of the best science job market journalists around

- WSJ Real Time Economics blog - focuses on a causal link between stagnant wages and guestworkers that I don't think we make, but is probably right

- Innovation Trail.org

-The Business Journal - on the opposition, with particular reference to the new computer science jobs estimated by the BLS. Generally I don't put much stock in these forecasts, but we ought to write up something on that.

- Science Insider hits the point that Ross Eisenbrey (VP of EPI) likes to emphasize about crowding out of domestic students from STEM.

- Huffington Post

- The Register

- Two posts on the Demos blog. This one is supportive. This one has a really odd criticism which verges on accusing us of not doing due diligence methodologically that I address in the comment thread.

- WBEZ

- My favorite so far, from Carney at CNBC - highlighted in the next post.

- Washington Post - good summary, with a focus on the shortage argument

- Slate (Matt Yglesias) - focus on shortage argument - a counter-argument that STEM guestworkers are good anyway but no attempt to explain why we should be uniquely happy to have STEM workers such that we'd give them a special visa

- Philadelphia Inquirer - a more labor protectionist take on the report, with special considerations about New Jersey

- Science Careers (here and here) - by one of the best science job market journalists around

- WSJ Real Time Economics blog - focuses on a causal link between stagnant wages and guestworkers that I don't think we make, but is probably right

- Innovation Trail.org

-The Business Journal - on the opposition, with particular reference to the new computer science jobs estimated by the BLS. Generally I don't put much stock in these forecasts, but we ought to write up something on that.

- Science Insider hits the point that Ross Eisenbrey (VP of EPI) likes to emphasize about crowding out of domestic students from STEM.

- Huffington Post

- The Register

- Two posts on the Demos blog. This one is supportive. This one has a really odd criticism which verges on accusing us of not doing due diligence methodologically that I address in the comment thread.

- WBEZ

- My favorite so far, from Carney at CNBC - highlighted in the next post.

Friday, April 26, 2013

No nursing shortages too?

I've been wanting to do more with the health workforce. I just got bad news from my Mathematica fellowship application where I would have done some of that, but perhaps at some other point.

Health is one area where labor shortages are more plausible - not because labor markets fail to work, but because demand growth is so strong and persistent you could imagine that the workforces are constantly struggling to keep up.

That's been my prior.

But apparently that might not be the case either. See WSJ reporting here and here.

The first link highlights why a closer distributional look might be important (a good point that a commenter made to me yesterday about our EPI work).

Health is one area where labor shortages are more plausible - not because labor markets fail to work, but because demand growth is so strong and persistent you could imagine that the workforces are constantly struggling to keep up.

That's been my prior.

But apparently that might not be the case either. See WSJ reporting here and here.

The first link highlights why a closer distributional look might be important (a good point that a commenter made to me yesterday about our EPI work).

Thursday, April 25, 2013

The estimable Ryan Murphy on the EPI paper

Here.

He says he largely agrees with Cowen's reaction so not surprisingly my reaction to Ryan is much the same as my reaction to Cowen (here). I largely agree with his thoughts but would put a somewhat different spin on it.

First, I'm interested in shortages and labor market adjustment because I'm a labor economist and the quirky things about these specialized labor markets are interesting to me (the fact that there's a lot of bad information out there is also a motivator).

Second, I agree with all the "moving out the PPF" stuff from Ryan and Tyler completely. I tend to think the bottleneck is on the demand-side and not the supply-side when it comes to STEM so I don't see giving a special visa to a bunch of IT guys as the way to do that. I take a long-term perspective on growth too. I'm not just thinking of the next Apple... I like to think about the next planet we settle too. For that, basic research features more prominently than it does in Ryan's post.

Third, I really don't like the "high skill immigration is good for poor natives" line. It's not that it's wrong or anything. It's fine as far as it goes. But if you think the minimum wage is a blunt instrument for helping poor Americans (and I do), then helping poor Americans by compressing the wage distribution through importing somewhat underpaid IT guys is a really blunt instrument for doing it. A cynic might suggest that this is what otherwise market-friendly economists tell themselves to feel better about manpower planning.

Like I said, I'm fine with the broad thrust that Ryan has here but would put it all just a little differently.

He says he largely agrees with Cowen's reaction so not surprisingly my reaction to Ryan is much the same as my reaction to Cowen (here). I largely agree with his thoughts but would put a somewhat different spin on it.

First, I'm interested in shortages and labor market adjustment because I'm a labor economist and the quirky things about these specialized labor markets are interesting to me (the fact that there's a lot of bad information out there is also a motivator).

Second, I agree with all the "moving out the PPF" stuff from Ryan and Tyler completely. I tend to think the bottleneck is on the demand-side and not the supply-side when it comes to STEM so I don't see giving a special visa to a bunch of IT guys as the way to do that. I take a long-term perspective on growth too. I'm not just thinking of the next Apple... I like to think about the next planet we settle too. For that, basic research features more prominently than it does in Ryan's post.

Third, I really don't like the "high skill immigration is good for poor natives" line. It's not that it's wrong or anything. It's fine as far as it goes. But if you think the minimum wage is a blunt instrument for helping poor Americans (and I do), then helping poor Americans by compressing the wage distribution through importing somewhat underpaid IT guys is a really blunt instrument for doing it. A cynic might suggest that this is what otherwise market-friendly economists tell themselves to feel better about manpower planning.

Like I said, I'm fine with the broad thrust that Ryan has here but would put it all just a little differently.

Cowen on the EPI report

Well the report has made it to perhaps the most important node in the entire economics blogosphere: Tyler Cowen. He has good thoughts that in a general sense I fully agree with, but I'd make a few additional points (which regular readers should be familiar with by now). I'll reproduce in full:

What he's really referring to is similar to what Arrow and Capron called a "social demand shortage": we simply think there ought to be more science done, period.

I agree we have such a social demand shortage, and I think science policy should be decided accordingly.

But the question for me is - exactly where is there a problem in the market provision of this socially optimal level of science? Generally speaking, all of the market failures economists identify that pertain to science and engineering are on the demand side, not the supply-side. Most of what Tyler lists are inputs (supply-side factors). Some are examples of demand (NIH funding, for example).

It seems to me there's no great market failure to speak of in the STEM labor market. It operates fine to meet the level of demand. There's no great market failure in the broadband manufacturing and installation market. The market works fine - it's problems on the demand side that are the hold up. The Super Collider wasn't shut down for supply side reasons. We could build the thing. It was shut down because the demand for it fell through. Why aren't we on Mars today? Not because we don't have the technology - because of the lack of demand.

There are lots of demand-side market failures associated with science that most of you are probably aware of. That's where the emphasis needs to be, IMO (and that includes NIH funding and the public decision to build things like supercolliders that Tyler mentions).

So that's my big-picture policy statement on STEM. Aside from big-picture stuff, though, I'll generally be talking about labor markets. That shouldn't be construed as me thinking that the other stuff is less important.

Via Matt, Hal Salzman, Daniel Kuehn, and Lindsay Lowell suggest there is no shortage because we do not observe significant wage rises for STEM workers. That’s a fact worth knowing and I am happy to praise the study in that regard. But it’s painting the basic worry into too narrow a box with its use of the word “shortage,” interpreted so literally.So my research interest is the STEM labor market. There's lots of good work on R&D investments and other elements that go into science and engineering, but my value-added is on the labor market side and I personally think it's fine to talk about shortage claims in that market.

The core claim is that STEM sectors will be those which produce the future social increasing returns for the economies which house them. If true (I am not trying to prejudge this), that means we should invest in both more STEM workers and more complementary inputs, whether that be particle colliders, NIH funding, the right broadband infrastructure, legalizing driverless cars, better IP law, tougher schools, or whatever. With the new, additional STEM workers, and the complementary inputs, America will (supposedly) be much better off.

To point out that the current supply of STEM workers stands in proper proportion to the other inputs suggests only that we are at a local optimum, not a global optimum. Similarly, it could have been pointed out that, before the rise of Hyundai, South Korea had just the right number of auto workers (not many) for their factories (also not many). That could have been true enough, but still investing in more auto factories and more auto workers was for Korea a very good path forward.

On top of all that, the report shows a worrying lack of concern about the notion of an economic margin. Even without boosts in the complementary inputs, more STEM workers still can be put to good use, even if there is no “shortage” today.

Here is a related post by Adam Ozimek.

What he's really referring to is similar to what Arrow and Capron called a "social demand shortage": we simply think there ought to be more science done, period.

I agree we have such a social demand shortage, and I think science policy should be decided accordingly.

But the question for me is - exactly where is there a problem in the market provision of this socially optimal level of science? Generally speaking, all of the market failures economists identify that pertain to science and engineering are on the demand side, not the supply-side. Most of what Tyler lists are inputs (supply-side factors). Some are examples of demand (NIH funding, for example).

It seems to me there's no great market failure to speak of in the STEM labor market. It operates fine to meet the level of demand. There's no great market failure in the broadband manufacturing and installation market. The market works fine - it's problems on the demand side that are the hold up. The Super Collider wasn't shut down for supply side reasons. We could build the thing. It was shut down because the demand for it fell through. Why aren't we on Mars today? Not because we don't have the technology - because of the lack of demand.

There are lots of demand-side market failures associated with science that most of you are probably aware of. That's where the emphasis needs to be, IMO (and that includes NIH funding and the public decision to build things like supercolliders that Tyler mentions).

So that's my big-picture policy statement on STEM. Aside from big-picture stuff, though, I'll generally be talking about labor markets. That shouldn't be construed as me thinking that the other stuff is less important.

Are we conflating IT and STEM?

Some commenters on Yglesias's post are not reading the report carefully (I know, I need to stop reading through comments). "10ured 4life" writes:

As for other fields, we've looked at that elsewhere (and cited the work in this report). Some are doing better than others. The life sciences are very glutted and have been for a while. The health sector (if you consider this STEM - definitions vary) is inhaling workers right now - it's doing fine. Other engineering fields we've looked at experience temporary shortages during the adjustment process. People find this in the literature all the time - run ups in wages due to positive demand shocks that take time to erode away because it takes students a few years to work through the educational system. In other words, the short run supply curve is inelastic and the long run supply curve is relatively elastic. A good recent example of this is petroleum engineering.

So not all fields are as glutted as the life sciences, but no study that I am aware of has turned up a finding of chronic shortages in a STEM field. Why? Because people respond to incentives. These are specialized fields so you can get a glut of workers with certain STEM skills, but it's very hard to find any evidence of chronic shortages.

As to his last point, that's a remarkable case. I don't have the employment rate for engineers out of college on hand. The non-employment rate is low but would still take up a good portion of his remaining 5 to 10%. Of those who do get jobs a year out of graduating, only 53% of engineers are working in engineering (the balance may be out of the engineering field by choice of course). These are not necessarily career jobs, but you'd think engineers would be considering an engineering job to be their "career job". So the idea that 90-95% of a class have career jobs before graduation is an enormous outlier. Maybe it's true, but it's not typical at all. Schools are notorious for gaming these sorts of numbers - I'd err on the side of not trusting it.

I clicked on the original paper: the authors are basically conflating IT and STEM. IT is clearly flat, but the rest of their is less clear.We're pretty clear on why we look at IT in the second half of the paper: the lion's share of high skill guestworkers go into IT. The inspector general of DHS called the L-1 "the computer visa". So after going over the STEM graduation numbers generally it made sense to look at IT specifically in relation to these visas. There's no conflation at all. We know they're different. If you're interested in the impact of these programs, look at the labor market where the programs are supplying workers.

Although this is anecdotal, the engineering school our our college is boasting that 90-95% of this year's graduating engineers already have their career jobs lined up a month before graduation...

As for other fields, we've looked at that elsewhere (and cited the work in this report). Some are doing better than others. The life sciences are very glutted and have been for a while. The health sector (if you consider this STEM - definitions vary) is inhaling workers right now - it's doing fine. Other engineering fields we've looked at experience temporary shortages during the adjustment process. People find this in the literature all the time - run ups in wages due to positive demand shocks that take time to erode away because it takes students a few years to work through the educational system. In other words, the short run supply curve is inelastic and the long run supply curve is relatively elastic. A good recent example of this is petroleum engineering.

So not all fields are as glutted as the life sciences, but no study that I am aware of has turned up a finding of chronic shortages in a STEM field. Why? Because people respond to incentives. These are specialized fields so you can get a glut of workers with certain STEM skills, but it's very hard to find any evidence of chronic shortages.

As to his last point, that's a remarkable case. I don't have the employment rate for engineers out of college on hand. The non-employment rate is low but would still take up a good portion of his remaining 5 to 10%. Of those who do get jobs a year out of graduating, only 53% of engineers are working in engineering (the balance may be out of the engineering field by choice of course). These are not necessarily career jobs, but you'd think engineers would be considering an engineering job to be their "career job". So the idea that 90-95% of a class have career jobs before graduation is an enormous outlier. Maybe it's true, but it's not typical at all. Schools are notorious for gaming these sorts of numbers - I'd err on the side of not trusting it.

Great comments on Yglesias's post

I can't seem to link to individual comments, but here are a few:

Area Man writes: "If you think there should be more immigrants, then fine. Increase immigration across the board, not just in one sector. This plan punishes people with STEM degrees but prevents them from reaping the benefits of having immigrants working in other sectors."And:

Dave writes: "Ok, I'll finally take the bait if I must.

This is just far too simplistic an argument, and I think you know it. If the question is on immigration in general, then the answer is yes, we need immigration in general.

But if the question is about whether we need discriminatory immigration to fill perceived shortages, the answer is an absolute no. This is the epitome of bad economic policy, and it is reverse logic.

The question should never be why special, activist economic policy is not such a bad thing, the question should be whether the perceived problem is so compelling as to require an intervention with an activist economic policy.

Clearly that standard is not and never was met. This was always about large corporations wanting the best labor as cheap as possible.

General vs. partial equilibrium and immigration again

One line one of my co-authors used during the conference call the other day was that STEM guestworkers putting downward pressure on native STEM wages was "econ 101". Indeed it is. I'm reminded of George Borjas's apt article title "The Labor Demand Curve is Downward Sloping".

But what sort of econ 101 is it?

The very important thing to realize is that it is partial equilibrium econ 101. It is what happens in a particular labor market when you increase the supply of workers.

That, of course, is not all there is to talk about. There's also general equilibrium. STEM immigrants buy bread and houses and medical services and gasoline and TVs. In that sense, they're going to reproduce demand patterns similar to native STEM workers and boost demand in the economy across a lot of markets at the same time that they're boosting supply in one particular labor market.

This goes for any immigrant.

So what's the point of distinguishing these general equilibrium and partial equilibrium effects?

If we have a wide-ranging increase in immigration flows that is not determined by Congressional gaming of the immigrant skill distribution, it's going to have a positive impact on aggregate demand and a positive impact on aggregate supply. The positive impact on demand is simply a consequence of the fact that everybody buys lots of different things.

So demand sort of takes care of itself. The only place where problems could really occur is if Congressional manipulation of the immigration flows gives us lots of partial equilibrium gluts and shortages by making life easier for some immigrant workers and harder for others.

The problem is the imbalance, not the immigration.

But what sort of econ 101 is it?

The very important thing to realize is that it is partial equilibrium econ 101. It is what happens in a particular labor market when you increase the supply of workers.

That, of course, is not all there is to talk about. There's also general equilibrium. STEM immigrants buy bread and houses and medical services and gasoline and TVs. In that sense, they're going to reproduce demand patterns similar to native STEM workers and boost demand in the economy across a lot of markets at the same time that they're boosting supply in one particular labor market.

This goes for any immigrant.

So what's the point of distinguishing these general equilibrium and partial equilibrium effects?

If we have a wide-ranging increase in immigration flows that is not determined by Congressional gaming of the immigrant skill distribution, it's going to have a positive impact on aggregate demand and a positive impact on aggregate supply. The positive impact on demand is simply a consequence of the fact that everybody buys lots of different things.

So demand sort of takes care of itself. The only place where problems could really occur is if Congressional manipulation of the immigration flows gives us lots of partial equilibrium gluts and shortages by making life easier for some immigrant workers and harder for others.

The problem is the imbalance, not the immigration.

Some press for the EPI high skill visa report

Washington Post

Science Careers

Slate (Matt Yglesias)

Been in contact with a couple other reporters, so more should be on the way. So far I like this coverage a lot - it is overwhelmingly focusing on the shortage issue and not visa volume issue. As I noted in the last post, there are really two policy conclusions that can be legitimately derived from this research: (1.) limit high skill guestworker visas, and (2.) don't limit guestworker visas, just stop giving high skill workers an advantage. EPI itself would probably be happy to see (1.) talked about more, but I'm personally glad they largely focus on the shortage issue.

Which brings me to Yglesias's discussion of the report (which I'm very appreciative of!). He writes:

By talking about "pecuniary externality on native born American STEM workers" he misses the point and abuses the term "externality" to boot (market competition is not an externality - I don't experience a negative externality because the rest of you bid up the price of gasoline that I have to pay). He misses the point because the problem isn't whether native STEM workers bear a cost or not - the problem is if there is a distortion in the native labor market that maybe a guided immigration policy could correct.

If not, then why emphasize STEM workers at all?

Science Careers

Slate (Matt Yglesias)

Been in contact with a couple other reporters, so more should be on the way. So far I like this coverage a lot - it is overwhelmingly focusing on the shortage issue and not visa volume issue. As I noted in the last post, there are really two policy conclusions that can be legitimately derived from this research: (1.) limit high skill guestworker visas, and (2.) don't limit guestworker visas, just stop giving high skill workers an advantage. EPI itself would probably be happy to see (1.) talked about more, but I'm personally glad they largely focus on the shortage issue.

Which brings me to Yglesias's discussion of the report (which I'm very appreciative of!). He writes:

"One of my more heterodox political views is that advocacy groups do themselves a disservice by adopting BS rhetoric that simply sounds good, because they leave themselves excessively vulnerable to attack. A great illustration comes today from an Economic Policy Institute study from Hal Salzman, Daniel Kuehn, and Lindsay Lowell that shows pretty persuasively that there's no real "shortage" of STEM workers in the American economy...My question to Matt Yglesias would be, why would you think that an influx of STEM workers is better than an influx of any other type of worker? What is it about STEM workers that we need to give them a special visa to come here, making it easier than it is for other people with other skill sets? One reason we might want to do this is if there were a shortage, but there's not a shortage. So what reason is left?

At the same time, if you'd just framed the case for skilled immigrants correctly in the first place I don't think this study does really any damage to it. An influx of STEM migrants is good for the migrants themselves. It's good for the fiscal posture of the United States and for the tax base of the localities in which the STEM workers reside. And it's good for people with complementary skills or occupations, whether that's journalists or dentists or barbers or waitresses or cab drivers or what have you. Whether or not STEM migrants impose some kind of pecuniary externality on native born American STEM workers, it's a good deal all things considered."

By talking about "pecuniary externality on native born American STEM workers" he misses the point and abuses the term "externality" to boot (market competition is not an externality - I don't experience a negative externality because the rest of you bid up the price of gasoline that I have to pay). He misses the point because the problem isn't whether native STEM workers bear a cost or not - the problem is if there is a distortion in the native labor market that maybe a guided immigration policy could correct.

If not, then why emphasize STEM workers at all?

Wednesday, April 24, 2013

My high skill visa report is now out at EPI

Guestworkers in the high-skill U.S. labor market: An analysis of supply, employment, and wage trends

By Hal Salzman, Daniel Kuehn, and B. Lindsay Lowell

We just finished a webinar for reporters, which went really well. Some big names in science reporting were there, someone from Bloomberg, and also WSJ. So hopefully this will get good press.

An important note I've mentioned before here: some groups of people are inevitably going to use this to advocate for fewer guestworker visas (indeed, it's the perspective of at least one of my co-authors). I think that's only one of at least two possible conclusions to draw from this work. The other position, which I hold, is that liberal immigration policy is a good thing and what is bad about high skill guestworker programs is that they pick and choose what sorts of immigrant workers have an easier time coming to the U.S., often as a result of bad analysis around alleged labor shortages. I mentioned this on the webinar and hopefully that shines through. Our presentation for reporters pretty solidly focused on the labor shortages question and the data on the guestworker flows.

I'm sure I'll talk more about this later, and share links to any commentary that comes out, but I've got a few other things to do right now.

By Hal Salzman, Daniel Kuehn, and B. Lindsay Lowell

We just finished a webinar for reporters, which went really well. Some big names in science reporting were there, someone from Bloomberg, and also WSJ. So hopefully this will get good press.

An important note I've mentioned before here: some groups of people are inevitably going to use this to advocate for fewer guestworker visas (indeed, it's the perspective of at least one of my co-authors). I think that's only one of at least two possible conclusions to draw from this work. The other position, which I hold, is that liberal immigration policy is a good thing and what is bad about high skill guestworker programs is that they pick and choose what sorts of immigrant workers have an easier time coming to the U.S., often as a result of bad analysis around alleged labor shortages. I mentioned this on the webinar and hopefully that shines through. Our presentation for reporters pretty solidly focused on the labor shortages question and the data on the guestworker flows.

I'm sure I'll talk more about this later, and share links to any commentary that comes out, but I've got a few other things to do right now.

Noah Smith on KrugTron

Click the link for the pictures, hang around for the commentary.

If this is an attempt to get undergraduates at Stony Brook to respect him, I think it may backfire. Still a good read.

Monday, April 22, 2013

Terrorism and rights

Nate Silver has some statistics on public views on Mirandizing terrorists, and it's depressing (although I suppose not surprising). On this particular case, I don't want to comment too specifically except to just make a blanket statement that I obviously think Tsarnev should be accorded the full protections of the Constitution. I hesitate to get outraged at what's happened so far simply because my experience with Law and Order leads me to have some vague recollection that they can hold someone for a while without arresting them while looking into things, and I'm not sure how that works exactly. But those legalities aside (which they should exploit to the fullest as long as it's legal), he needs to be Mirandized if we're going to hold him.

This is not to say that all terrorists need to be Mirandized. If you have someone sent as a part of an orchestrated attack on the United States and they can therefore be reasonably designated as an enemy combatant, give them the Constitutional due process of an enemy combatant rather than the Constitutional due process of an accused felon by all means. But that needs to be established - as the Supreme Court told Bush - and I don't think some youtube videos posted by Tsarnev's brother establishes it. The military can always step in later and take custody of him if it looks like it makes sense to treat him as an enemy combatant.

Of course I may not know everything and they may already have all this information.

[UPDATE: Also, I heard he is currently unconscious? Is that true? Is it possible he is not Mirandized because of concerns around Mirandizing an unconscious person (how can we be sure he know his rights?)]

Also on rights:

- Obviously what happened on Friday (to say nothing of Monday) is something we're still all learning about, but my impression at the moment is that the lockdown was probably a policy mistake rather than a Constitutional mistake (as some people are framing it), at least when it comes to the whole city of Boston. My best understanding is that it was nothing like martial law and it was a request not an order, but I do find it a little absurd that areas outside Watertown were locked down at all. A general "be safe and report anything suspicious" probably would have sufficed outside of Watertown. This isn't meant to minimize the announcement. Just because it wasn't a Constitutional travesty doesn't mean it wasn't problematic. Knee-jerk reactions like that by government set precedents. I'm not especially worried about this reaction sending us down the road to serfdom, but I still think it was a mistake.

- As I understand it the door to door searches in Watertown generally happened with permission, so no fourth amendment issue there whatsoever. Those strange cases where residents did not give permission (I imagine most did - who wouldn't?) seem to have exigent circumstances attached which means it's also not a fourth amendment violation. This case is basically made by Katy Waldman at Slate too.

So generally speaking my biggest Constitutional concern right now is how they treat Tsarnev. I don't have a whole lot of those concerns around the search itself, although much of the search was probably ill-advised.

This is not to say that all terrorists need to be Mirandized. If you have someone sent as a part of an orchestrated attack on the United States and they can therefore be reasonably designated as an enemy combatant, give them the Constitutional due process of an enemy combatant rather than the Constitutional due process of an accused felon by all means. But that needs to be established - as the Supreme Court told Bush - and I don't think some youtube videos posted by Tsarnev's brother establishes it. The military can always step in later and take custody of him if it looks like it makes sense to treat him as an enemy combatant.

Of course I may not know everything and they may already have all this information.

[UPDATE: Also, I heard he is currently unconscious? Is that true? Is it possible he is not Mirandized because of concerns around Mirandizing an unconscious person (how can we be sure he know his rights?)]

Also on rights:

- Obviously what happened on Friday (to say nothing of Monday) is something we're still all learning about, but my impression at the moment is that the lockdown was probably a policy mistake rather than a Constitutional mistake (as some people are framing it), at least when it comes to the whole city of Boston. My best understanding is that it was nothing like martial law and it was a request not an order, but I do find it a little absurd that areas outside Watertown were locked down at all. A general "be safe and report anything suspicious" probably would have sufficed outside of Watertown. This isn't meant to minimize the announcement. Just because it wasn't a Constitutional travesty doesn't mean it wasn't problematic. Knee-jerk reactions like that by government set precedents. I'm not especially worried about this reaction sending us down the road to serfdom, but I still think it was a mistake.

- As I understand it the door to door searches in Watertown generally happened with permission, so no fourth amendment issue there whatsoever. Those strange cases where residents did not give permission (I imagine most did - who wouldn't?) seem to have exigent circumstances attached which means it's also not a fourth amendment violation. This case is basically made by Katy Waldman at Slate too.

So generally speaking my biggest Constitutional concern right now is how they treat Tsarnev. I don't have a whole lot of those concerns around the search itself, although much of the search was probably ill-advised.

Assault of thoughts - 4/22/2013

"Words ought to be a little wild, for they are the assault of thoughts on the unthinking" - JMK

- Miles Kimball shares gender and labor market tweets, including a recent one by me

- Razib Kahn on a Bill Maher clip comparing Muslim and Christian fundamentalism, but even more importantly how these groups fare under American secularism vs. the alternatives

- A nice sentiment, but screw Jupiter. I can't grow a garden on Jupiter.

- Couldn't agree more with Alex Tabarrok on apprenticeships.

-Regular reader Blue Aurora has informed me that Michael Emmett Brady has had his article on Keynes and Boole published in the History of Economic Ideas.

- Miles Kimball shares gender and labor market tweets, including a recent one by me

- Razib Kahn on a Bill Maher clip comparing Muslim and Christian fundamentalism, but even more importantly how these groups fare under American secularism vs. the alternatives

- A nice sentiment, but screw Jupiter. I can't grow a garden on Jupiter.

- Couldn't agree more with Alex Tabarrok on apprenticeships.

-Regular reader Blue Aurora has informed me that Michael Emmett Brady has had his article on Keynes and Boole published in the History of Economic Ideas.

Saturday, April 20, 2013

Immigration open thread

Does anyone have thoughts on the new proposal, particularly the guestworker side?

I haven't gotten a chance to look closely at it. The W visa (for low skill workers) is interesting. Part of it is nice because it's a ham-fisted attempt at not making distinctions between different types of guestworkers the way the current high skill programs do. But part of it is frustrating because I just think "how about instead of H-1B, H-2B, L-1, W, etc. etc. we just have a single (we can call it A-1 for you steak fans) guestworker visa that doesn't distinguish between workers?".

The answer to that question, of course, is that some people still want to treat different workers differently.

From what I do know about the W visa it's basically like the high skill visas in the bill, but without any of the perks...

...because it would be totally unconscionable to treat low skill workers with the same dignity and benefits as high skill workers, right?!?

On top of that, it seems like a lot of the old problems aren't fixed, and some are even made worse by some kind of STEM exception that I need to learn more about (and is apparently a little vague in its own right).

We've been here before - it's true of any overarching reform. Some things are better, some things are worse. That's how I felt about health reform too. My assessment with health reform was "this is a step in the right direction that we can work with and more is better than is worse". I'm still trying to figure out if that's my assessment of the immigration reform options.

Then again, given yesterday's events it may unfortunately be a moot point.

My EPI briefing paper on high skill guestworkers should come out next week. There was a slight delay for editorial reasons.

I haven't gotten a chance to look closely at it. The W visa (for low skill workers) is interesting. Part of it is nice because it's a ham-fisted attempt at not making distinctions between different types of guestworkers the way the current high skill programs do. But part of it is frustrating because I just think "how about instead of H-1B, H-2B, L-1, W, etc. etc. we just have a single (we can call it A-1 for you steak fans) guestworker visa that doesn't distinguish between workers?".

The answer to that question, of course, is that some people still want to treat different workers differently.

From what I do know about the W visa it's basically like the high skill visas in the bill, but without any of the perks...

...because it would be totally unconscionable to treat low skill workers with the same dignity and benefits as high skill workers, right?!?

On top of that, it seems like a lot of the old problems aren't fixed, and some are even made worse by some kind of STEM exception that I need to learn more about (and is apparently a little vague in its own right).

We've been here before - it's true of any overarching reform. Some things are better, some things are worse. That's how I felt about health reform too. My assessment with health reform was "this is a step in the right direction that we can work with and more is better than is worse". I'm still trying to figure out if that's my assessment of the immigration reform options.

Then again, given yesterday's events it may unfortunately be a moot point.

My EPI briefing paper on high skill guestworkers should come out next week. There was a slight delay for editorial reasons.

Friday, April 19, 2013

The Boston terrorists and immigration

Well it has entered the immigration debate, just as 9-11 did. So far, the ties made by guys like Grassley seem to me to be both vague and stupid.

Which is not to say that there isn't a more precise and more intelligent lesson for immigration policy in all this.

I think there is, but it's a lesson for a much narrower group of open border advocates. Some people who advocate openness oppose the visa process itself and think that no one should have to seek permission to come here. The government has no business keeping anyone out. This group quite literally wants open borders. No visas obviously also means no border security. Cases like this demonstrate why that might be a bad idea. Even if you support an open United States, it's probably still of value to check people out, identify a family or employer sponsor, and keep records.

I'll take a second to anticipate a red herring: of course this isn't going to prevent every incident. It obviously didn't prevent this incident, or 9-11 for that matter.

That misses the point. Good policy analysis thinks about these things on the margin and it considers the counterfactual. On the margin having some order to a policy of open immigration will improve security. The counterfactual case with no formal immigration process would make it far easier for terrorists, cartels, or anyone with bad intent to enter the country.

So that's not the sort of message that I suspect Grassley was trying to send, but it is a worthwhile point for literal open border types to consider.

Which is not to say that there isn't a more precise and more intelligent lesson for immigration policy in all this.

I think there is, but it's a lesson for a much narrower group of open border advocates. Some people who advocate openness oppose the visa process itself and think that no one should have to seek permission to come here. The government has no business keeping anyone out. This group quite literally wants open borders. No visas obviously also means no border security. Cases like this demonstrate why that might be a bad idea. Even if you support an open United States, it's probably still of value to check people out, identify a family or employer sponsor, and keep records.

I'll take a second to anticipate a red herring: of course this isn't going to prevent every incident. It obviously didn't prevent this incident, or 9-11 for that matter.

That misses the point. Good policy analysis thinks about these things on the margin and it considers the counterfactual. On the margin having some order to a policy of open immigration will improve security. The counterfactual case with no formal immigration process would make it far easier for terrorists, cartels, or anyone with bad intent to enter the country.

So that's not the sort of message that I suspect Grassley was trying to send, but it is a worthwhile point for literal open border types to consider.

Piled Higher and Deeper uses ATUS Data!

...sort of.

A deep and passionate love affair between myself and this dataset blossomed last fall. Any day now I should hear back from Mathematica about whether I will be given money and office space to play around more with it this summer. It's pretty competitive, but I think my proposal was too.

A deep and passionate love affair between myself and this dataset blossomed last fall. Any day now I should hear back from Mathematica about whether I will be given money and office space to play around more with it this summer. It's pretty competitive, but I think my proposal was too.

One of the most ridiculous reactions to terrorism in Boston...

...is to point out that more people choke on chicken bones or drown in latrines or bleed out from paper cuts in a year than die in terrorist attacks.

This is life. No one gets out of it alive. When someone takes it during a celebratory event, that's different - particularly when it terrifies a lot of people.

Other ridiculous reactions are to equate (1.) the killing of the innocent with the killing of the guilty, and (2.) the unintentional killing of the innocent with the intentional and long-premeditated killing of the innocent.

What is wrong with our moral compass that this claptrap always seems to get churned up in the wake of a tragedy?

At least the conspiracy theorists that talk about false flags have their basic moral intuition straight. They're just bizarrely credulous and paranoid. That's not good, of course, but for the most part they seem to be able to make the distinctions outlined above.

UPDATE: This is like saying "Arson? Why are you so upset about arson? Do you realize how many more fires are started by accident in a year? Way more than are started by arsonists! It's really terrible that people get so worked up by and want to do something about arsonists."

This is life. No one gets out of it alive. When someone takes it during a celebratory event, that's different - particularly when it terrifies a lot of people.

Other ridiculous reactions are to equate (1.) the killing of the innocent with the killing of the guilty, and (2.) the unintentional killing of the innocent with the intentional and long-premeditated killing of the innocent.

What is wrong with our moral compass that this claptrap always seems to get churned up in the wake of a tragedy?