A lot of people have been discussing Krugman's comparison of the American stimulus to European countries, and I have a few scattered reactions I wanted to share on it.

I should preface all that, though, by saying that I don't really like these posts much from Krugman anyway. It's not that there's anything necessarily wrong with the approach, it's just so hard for me to know what to make of them. One of the posts that's been discussed compares the U.S. to Sweden, for example. What does this tell us exactly? To know what it tells us you have to know what would have happened in both Sweden and the U.S. without the government spending that went on. I feel like I have a rough sense of what I'd expect in the U.S., but no idea when it comes to Sweden. You have to know something about the monetary policy stance (I don't know that for Sweden), and you have to know what was going on in the financial sector (I don't know that for Sweden), and aside from those two elephants in the room you have to know exactly what was going on in the economy. I don't, so I really don't get much from these sorts of posts. My RSS feed is pretty long, so often (knowing I'm not going to feel like I get much out of it), I even skip over these posts.

But I do think there are a few things to say about some of this ongoing conversation.

I. What data to look at?

That can be a tough call, but generally I think:

1. You can't just look at deficits. You have to look at expenditures, but probably deficits and expenditures together.

J.R. Vernon does a great job - in reviewing some empirical work by Christina Romer - highlighting why this is critical. Tax multipliers and spending multipliers are different because of differences in public and private MPCs. Looking at deficits therefore

understates the fiscal stance.

2. You

can look at any level of government spending, because what we're concerned with is marginal effects. Another dollar of spending by the Department of the Interior is going to increase output for Keynesian reasons, after all. But do you

want to look at just any old measure of government spending? I don't think so. If we're talking about government policy it seems to me that we should look at total government spending (i.e. - federal, state, and local), but of course that's a judgement call. We think of state and local government as "government" in almost every other discussion. Much of the federal stimulus went to state and local governments. And most critically

state and local expenditures are determined politically and not by the market. Ultimately I think you just need to be clear about what your claim is.

3. I am suspicious of looking at things as a percent of GDP (although I'm sure I do it a lot). We're looking at cases where output is shrinking. Think of what government spending as a percent of GDP would look like if government did nothing and the economy shrank. If you're looking at a percentage of GDP you would say the government was stimulating the economy. That makes no sense at all. Nobody is claiming that having the government take up a larger share of the economy is inherently a good thing. The claim is that increased demand is a good thing.

4. Getting a sense of the trend is always important. Growth below trend seems like austerity to me.

II. Krugman's Ireland Post

Krugman had

a post recently looking at Irish austerity. I liked it better than most because it basically said "

hey - the Irish are doing austerity", rather than trying to make any kind of multiplier point which, as I said above, I'm uncomfortable with. Bob Murphy

didn't like it. Russ Roberts

didn't like it either. It's true I've pretty much given up on Russ, but I thought this post was especially bad. Krugman seemed to be saying two correct things: (1.) that the increase in spending in Ireland earlier in the crisis was the bank bailouts which may or may not be a good financial rescue package, but certainly isn't what we typically think of as Keynesian stimulus, and (2.) welfare program growth has not been due to any alterations of the welfare state. Russ seemed to think he said that welfare program growth does not count as stimulus. I still can't find where he said that. I emailed Bob about it and I think it's a difference in interpretation (and of course, I think what I think is clearly right).

The takeaway of this post is that once you take out the transfers to the banks, Irish spending has been flat through the crisis (even taking into account the increase in welfare spending, since other spending declined). Essentially standing still (i.e. - below trend) as your economy collapses is austere.

III. Swedish Stimulus

There's also been a lot of acrimony over

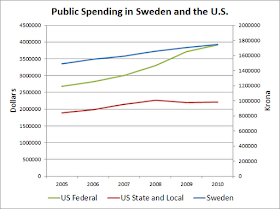

Krugman's Sweden post. To repeat my point from above, I'm a little hesitant to get too excited either way over this since I have no idea what's going on with Swedish money or Swedish banking. But Krugman seems basically right that Sweden doesn't seem to have been all that austere. I took a look at

OECD data, and Swedish public spending growth seems about on par with the U.S. from 2005 to 2010 (they haven't posted data after that, but that's the heart of the crisis). It seems to be growing somewhat slower than U.S. federal spending (

Bob posts federal spending too) and faster than U.S. state and local spending. It works out to low single digit annual growth rates.

I would caution one thing about this data - like the Irish data, it includes capital transfers. That's a decent share of U.S. federal growth (6.051% of U.S. federal spending in 2009), but not a big part of the Swedish growth (0.508% of Swedish public spending in 2009). So if we're talking about spending that we normally think of as stimulus (spent on output, not stocks of assets) maybe Sweden was even less austere than the U.S. I don't have time to do all the comparisons now.

But the difference in capital transfers also gets at one of the elephants in the room I mentioned earlier: I don't think Sweden had a banking crisis. That matters tremendously if we are talking about post-recession growth trends. It probably makes all this talk of public spending levels superfluous.

To wrap up Sweden,

LK has a good post on it this morning, and he makes an important point: a good initial response lets you get back to standard fiscal policy sooner.

I know people are going to say

what they've said many times before: that I am letting Krugman off the hook because... I'm not sure why. I'm not sure what they think I gain by being easy on Krugman. That's not what's going on here. I honestly don't see the big problem with Krugman's posts. I probably wouldn't have posted so much about it, for the reasons I stated above. But I don't see any great malfeasance.

I would say this: Sweden certainly doesn't provide any evidence that shakes my faith in Keynesianism. Granted, a couple Swedish data points don't provide a super clear picture either.