If you're friends with Steve Horwitz on facebook you know that there's lots of talk about feminism going on on his page right now, with origins in this BHL post by Sarah Skwire. I don't want to talk about those discussions specifically, but I thought I'd provide a quick review post on feminist economics.

For those of you that don't know, gender economics is one of my two fields for my PhD (the other being labor economics). A lot of gender economics is labor economics, which is one thing I liked about it. It's also concerned with questions of economic disparities which has long been a research interest of mine as it relates to race, so gender was something that I was interested in specializing in as well. It's also a strength of American University's department, so it seemed like something worth taking advantage of.

Feminist economics is generally conceived of a heterodox approach, and this is the sense in which I am least able to be classified as a "feminist economist". As you all know, even when I like the contrinbutions of different heterodoxies I still think the criticisms of mainstream methodology fall a little flat, and feminist critiques are no exception. I don't want to diminish dedicated feminist methodologists, but I would describe their critiques as boilerplate heterodox stuff. I do think that insofar as we're calling feminist methodology just a call for mixed methods and heterodox modeling techniques in addition to solid mainstream methodology I fully support that. Insofar as it's a critique of mainstream methodology I'm less enthusiastic.

OK - methodology and my reservations are out of the way. What do feminist economists work on?

The obvious questions are also some of the most important: gender wage gaps, occupational segregation, discrimination, etc. None of this is foreign to mainstream economists who never heard of feminist economics but were just interested in gender.

In addition to those issues you have a research agenda preoccupied with critical issues that are not usually treated by the mainstream, including care, unpaid work and home production, household bargaining. Household bargaining is pretty darn mainstream, I guess - but it's central to feminist economics. One of the most compelling things about feminist economics is that these central issues make up a lot of our lives, and they are amenable to economic analysis.

All of these are relatively amenable to mainstream economic methods. In fact usually what you have is a critique of one or two assumptions made in the mainstream literature, followed by the application of mainstream thinking (sans that particular assumption) to the problem.

As far as my work in this field, I have a paper I should be submitting next week on time spent in home production over the business cycle. I'm currently writing a paper on occupational segregation in the sciences. I'm also preparing a proposal for a summer fellowship on the labor supply effect of care work (for elderly family members).

The Feminist Economics web page is here.

The American Univeristy gender economics page is here.

Nancy Folbre's website is here.

Stephanie Seguino's website is here.

Frances Woolley's website is here.

Thursday, February 28, 2013

Norm Matloff has an EPI briefing paper on high skill immgiration

Here.

Matloff has grown on me over time. He is a math PhD and a computer science professor, so I had a lot of trouble at first with how he framed and thought about things, but making an adjustment for that difference of perspectives I've appreciated him more (not that I concede his is always the best way of approaching a question).

Haven't read this briefing paper yet, but it looks like it's similar to things of his I have read and talks I've seen him give. Peoples' sense of the composition of the high skill immigrant population is often skewed and he addresses some of those questions.

Matloff has grown on me over time. He is a math PhD and a computer science professor, so I had a lot of trouble at first with how he framed and thought about things, but making an adjustment for that difference of perspectives I've appreciated him more (not that I concede his is always the best way of approaching a question).

Haven't read this briefing paper yet, but it looks like it's similar to things of his I have read and talks I've seen him give. Peoples' sense of the composition of the high skill immigrant population is often skewed and he addresses some of those questions.

Noah Smith on immigration

Here. I don't have time to provide thoughts in detail but you can probably anticipate them.

He makes the case against labor protectionism: good.

He makes the case for high skill favoritism: bad.

He disputes some things from Dean Baker: I'll leave that one to Dean, who suggests he'll write more.

I am neck-deep in these issues right now, working on a briefing paper that hopefully you'll hear more about in the coming weeks (this ought to be quicker than the process at Urban, I think). Needless to say, the more I learn about the existing high skill programs the more I dislike them (which is not to say that I dislike high skill immigration).

My dream policy is a relatively open system with a guestworker and permanent component (with strong family-based provisions), with no picking and choosing on the guestworker side of which types of guestworkers we prefer, full portability of guestworker visas.

In the absence of that dream policy there is a lot to clean up in treatment of undocumented residents and a whole lot to clean up in high skill guestworker programs.

First and foremost I'm interested in the economics of these questions and not the politics (just because that's my area not because I think the politics are unimportant), and so I truly bristle at invocations of labor shortages to justify high skill visas.

He makes the case against labor protectionism: good.

He makes the case for high skill favoritism: bad.

He disputes some things from Dean Baker: I'll leave that one to Dean, who suggests he'll write more.

I am neck-deep in these issues right now, working on a briefing paper that hopefully you'll hear more about in the coming weeks (this ought to be quicker than the process at Urban, I think). Needless to say, the more I learn about the existing high skill programs the more I dislike them (which is not to say that I dislike high skill immigration).

My dream policy is a relatively open system with a guestworker and permanent component (with strong family-based provisions), with no picking and choosing on the guestworker side of which types of guestworkers we prefer, full portability of guestworker visas.

In the absence of that dream policy there is a lot to clean up in treatment of undocumented residents and a whole lot to clean up in high skill guestworker programs.

First and foremost I'm interested in the economics of these questions and not the politics (just because that's my area not because I think the politics are unimportant), and so I truly bristle at invocations of labor shortages to justify high skill visas.

Animal spirits comment of the day

From PrometheeFeu: "Crazy rich people have often played a role in pushing the boundaries of the known world by doing crazy things which any rational analysis should advise against even though somebody really needed to do those things."

The subject at hand is Mars.

The subject at hand is Mars.

Wednesday, February 27, 2013

I sometimes get the urge to pick up Amity Shlaes...

...the copy of The Forgotten Man on my shelf, the new Coolidge book in the bookstore.

She writes about things that interest me. She also has a different perspective and it's always good to read different perspectives.

But thankfully, Brad DeLong pulls me back from the brink.

The trouble with Shlaes is that although she writes history - and probably is pretty good at tracking down that history - she always seems to have a moral-of-the-story she wants to give you and in fact it's always the same moral-of-the-story. Having a thesis or viewpoint is one thing, but having a political statement you're always trying to get across is fairly worthless in a historian.

She writes about things that interest me. She also has a different perspective and it's always good to read different perspectives.

But thankfully, Brad DeLong pulls me back from the brink.

The trouble with Shlaes is that although she writes history - and probably is pretty good at tracking down that history - she always seems to have a moral-of-the-story she wants to give you and in fact it's always the same moral-of-the-story. Having a thesis or viewpoint is one thing, but having a political statement you're always trying to get across is fairly worthless in a historian.

What do you think of a 2018 launch for a manned Mars fly-by?

Here.

As opposed to a landing.

And libertarian readers - don't click through the link, see who's doing it, and just tell me that you're OK with any space exploration as long as it's done privately and not by the government. That's a boring answer. I doubt that distinguishes you from anyone on Earth (who actually thinks people shouldn't be allowed to use their own money to do shit in space?).

What about the fly-by aspect of it?

On the one hand, it's a let down from the ultimate goal. On the other hand, this would be many orders of magnitude farther than any human has been from the planet. Our sense of our world will expand, and that could pave the way for landings.

My initial reaction was non-chalance/disappointment, but I very quickly became more excited. Five years. Leaving for Mars in five years.

As opposed to a landing.

And libertarian readers - don't click through the link, see who's doing it, and just tell me that you're OK with any space exploration as long as it's done privately and not by the government. That's a boring answer. I doubt that distinguishes you from anyone on Earth (who actually thinks people shouldn't be allowed to use their own money to do shit in space?).

What about the fly-by aspect of it?

On the one hand, it's a let down from the ultimate goal. On the other hand, this would be many orders of magnitude farther than any human has been from the planet. Our sense of our world will expand, and that could pave the way for landings.

My initial reaction was non-chalance/disappointment, but I very quickly became more excited. Five years. Leaving for Mars in five years.

It's so nice not to have to listen to Ron Paul questioning Bernanke

Politicians talking down from on high at witnesses is obnoxious enough - politicians thinking they know economics and talking down from on high at witnesses that actually do know economics are particularly obnoxious.

High skilled immigration

- Bipartisan consensus on STEM labor shortages - the first sign of a problem with the idea:

-

- Daniel Costa of EPI on STEM labor shortage claims

-

- Daniel Costa of EPI on STEM labor shortage claims

Tuesday, February 26, 2013

Excellent sentences from Don Boudreaux

Here.

I share Don's skepticism, later in the post, of the idea that general equilibrium is what is driving observed positive or non-existent minimum wage effects on employment. I said this the other day, too. A general equilibrium story that says minimum wages help the whole economy is more plausible than that. But the strongest theoretical explanations for the emploument effect are partial equilibrium ones in this case I think.

We have a few good partial equilibrium stories - some that predict positive effects and some that predict negative effects. Good empirical design handles the ceteris paribus, and what comes out helps us to arbitrate between our theoretical possibilities.

"Mr. Forester is exactly correct that ceteris paribus seldom, if ever, holds true in reality – especially in social and economic reality. And this fact is precisely why ceteris paribus theorizing is so crucial. Our theories are meant to give us mental pictures of parts of reality. To take mental snap shots of any part of reality that we wish to better understand, we cannot rely upon reality itself to isolate for us those parts of itself – those parts of reality – that we’re most interested in understanding. So we theorize, and in theorizing we economists (as do all scientists) use ceteris paribus restrictions. To use such restrictions is no sign that the scientist really believes that ceteris is paribus - or that ceteris should be paribus. To use such restrictions is simply an unavoidable part of thinking seriously about an ever-changing and complex reality.The first two paragraphs are more highly recommended than the third here. I have no idea why he thinks we ought to privilege partial over general equilibrium theories. I also don't see the general equilibrium stories that get told as being any more "just so stories" than the partial equilibrium stories out there. In fact if anything people are too quick to stop thinking at the end of a naive partial equilibrium story.

Mr. Forester is also correct that (and here I use economists’, not his, terms) partial-equilibrium analysis differs from general-equilibrium analysis. Understanding a part of the economy, working in isolation, is not necessarily to understand that part of the economy as it is connected to the larger economy. What is true for that part of the economy M were it isolated from the rest of the economy might well not be true for that part of the economy M when the effects of changes in M extend outward to other parts and then, in turn, the reactions from the other parts of the economy work their way back to affect M.

But in order to legitimately dismiss the lessons of partial-equilibrium analysis because of alleged contrary feedback from the larger, general economy, one needs more than just-so stories or hypotheticals."

I share Don's skepticism, later in the post, of the idea that general equilibrium is what is driving observed positive or non-existent minimum wage effects on employment. I said this the other day, too. A general equilibrium story that says minimum wages help the whole economy is more plausible than that. But the strongest theoretical explanations for the emploument effect are partial equilibrium ones in this case I think.

We have a few good partial equilibrium stories - some that predict positive effects and some that predict negative effects. Good empirical design handles the ceteris paribus, and what comes out helps us to arbitrate between our theoretical possibilities.

Monday, February 25, 2013

No, it's not an existential crisis - but that doesn't mean it's not a bad idea

The line I've been hearing from sophisticated and unsophisticated commenters alike (that's when it really concerns me) these days is to mock sequester because it's not an "existential crisis" (yes I've seen that phrase at least onc) - that it's not the horror show we're told it's going to be.

It's a classic strawman. Nobody said it was going to be an existential crisis, of course. Nobody said there will be blood in the streets. But the fringe that actually likes this is using that line to trivialize it.

The thing is, it doesn't have to be an existential crisis to be a bad idea. The economy is growing right now, just like they all love to point out that government spending will still grow after sequester. The economy doesn't present us with an existential crisis. We aren't all wasting away in the streets right now (some people are, and services to them will be weakened by sequester, but let's put that aside for now). Does that mean the economy isn't in bad shape? Of course not. So let's cut this rhetorical trick out.

95% of economists apparently agree that sequester will be bad for the economy. The consensus against the minimum wage is nowhere near that, and I've been told repeatedly that I'm abandoning econ 101 even in just shrugging my shoulders at the minimum wage (as regular readers know I haven't exactly been a cheerleader for it).

Second only to cutting spending so much in a recession in stupidity is that the cuts we're doing don't even hit the genuine problems with the budget. We do have budget and debt problems. The problems leading up to now have largely been the Bush tax cuts and the unfunded war spending. The tax cuts were partially dealt with (again, though, not the wisest thing to do in a recession). The biggest problems going forward are the entitlement programs.

And guess what two major spending categories are exempt from sequester?

Direct war spending and entitlement spending.

It's insane. If you're one of the ones going around saying this is a good idea my confidence that you are actually concerned about fiscal responsibility has gone down.

It's not an existential threat, but it's bad policy.

It's a classic strawman. Nobody said it was going to be an existential crisis, of course. Nobody said there will be blood in the streets. But the fringe that actually likes this is using that line to trivialize it.

The thing is, it doesn't have to be an existential crisis to be a bad idea. The economy is growing right now, just like they all love to point out that government spending will still grow after sequester. The economy doesn't present us with an existential crisis. We aren't all wasting away in the streets right now (some people are, and services to them will be weakened by sequester, but let's put that aside for now). Does that mean the economy isn't in bad shape? Of course not. So let's cut this rhetorical trick out.

95% of economists apparently agree that sequester will be bad for the economy. The consensus against the minimum wage is nowhere near that, and I've been told repeatedly that I'm abandoning econ 101 even in just shrugging my shoulders at the minimum wage (as regular readers know I haven't exactly been a cheerleader for it).

Second only to cutting spending so much in a recession in stupidity is that the cuts we're doing don't even hit the genuine problems with the budget. We do have budget and debt problems. The problems leading up to now have largely been the Bush tax cuts and the unfunded war spending. The tax cuts were partially dealt with (again, though, not the wisest thing to do in a recession). The biggest problems going forward are the entitlement programs.

And guess what two major spending categories are exempt from sequester?

Direct war spending and entitlement spending.

It's insane. If you're one of the ones going around saying this is a good idea my confidence that you are actually concerned about fiscal responsibility has gone down.

It's not an existential threat, but it's bad policy.

Sunday, February 24, 2013

Great sentences on the minimum wage

From Bill Woolsey. I'm not sure about the end of this one way or the other but its an interesting thought:

The wage discrimination point in the post is important to consider too, although its relative prevalence is obviously an empirical question (I'm guessing these places for the minimum wage discussion have take-it-or-leave it wage structures).

"My vision of the real world is that it is rife with monopoly, monopsony, and all sorts of price and wage discrimination. But, this is in the context of lots of compeition. Competition is "imperfect," but the gains and losses in efficiency are small and fleeting in world of creative distruction.Our estimates are pooled across labor markets and firms. A zero effect really just means we've got about as many going one way as the other.

Still, I wouldn't be surprised if the monopsony effect resulted in some firms hiring more workers due to a higher minimum wage. Unfortunately, that same increase in the minimum wage will push the wage above the marginal revenue product of labor for other firms so that they hire fewer workers.

The notion that government operates like an omniscient benevolent despot and could and would set a wage in each and every market so that competitive equilibrium is approximated is completely unrealistic. I think a more plausible starting place would be politicians trading off the loss of employment versus the increase in wage income. That would suggest that minimum wages would be set above the marginal revenue product of the current level of employment. Of course, reduced profits to firms, very significant politically relevant short run, and even higher prices to those purchasing the products might relevant."

The wage discrimination point in the post is important to consider too, although its relative prevalence is obviously an empirical question (I'm guessing these places for the minimum wage discussion have take-it-or-leave it wage structures).

A DDD example minimum wage study

In a previous post I mentioned DDD designs as a similar strategy to controlling for state-specific time trends (along with matched DIDs). David Rosnick - a classmate of mine at GW and now at CEPR - emailed this DDD analysis he did for CEPR.

I feel like I know Washington pretty well, and I think they do care about the deficit

Evan Soltas wrote about this recently, but I don't think he has it quite right. He has some good point about differences between Democrats and Republicans and I do think that matters. There are good and bad things about Washington and the deficit relative to the rest of the country (and by "Washington" I'm talking about politicians, federal workers, politicos, advocates, and policy analysts - five very different groups of people. I'm the last one and I'm married to the second one and the other three regularly infuriate me).

Some good things about Washington and the budget:

- Most people in Washington understand that you don't need to balance the budget, you just need to keep the debt sustainable. Most economists understand this too. Many Americans don't seem to. Most people in Washington do genuinely want to do this.

- Most people in Washington seem to be able to distinguish between long-term and short-term budget problems. This is also something that you are less likely to see outside of Washingon.

- Fewer people in Washington, but still probably more than in the rest of the country, understand where the debt problems come from: Medicare, not Social Security; war spending, not foreign aid.

Some bad things about Washington and the budget:

- Politicians, politicos, and advocates achieve their goals by muddying up the previous three bullet points when talking to the public. There are a select few advocates specifically concerned with the budget and a politician here and there that break this pattern.

- Politicians, politicos, and advocates who do care about the deficit care even more about how they're going to fix the deficit. This is where Evan was on to something. Democrats want to do it one way and Republicans want to do it another. The end result comes out of a political process and usually makes less sense (from a budget perspective) than either side's individual plan (although sometimes those individual plans don't make sense). Nuances like long vs. short term or macroeconomic conditions usually go completely out the window during the political process. So it's not really an issue of whether Washington cares: they do. It's an issue of what the institutions in Washington do with that.

Some good things about Washington and the budget:

- Most people in Washington understand that you don't need to balance the budget, you just need to keep the debt sustainable. Most economists understand this too. Many Americans don't seem to. Most people in Washington do genuinely want to do this.

- Most people in Washington seem to be able to distinguish between long-term and short-term budget problems. This is also something that you are less likely to see outside of Washingon.

- Fewer people in Washington, but still probably more than in the rest of the country, understand where the debt problems come from: Medicare, not Social Security; war spending, not foreign aid.

Some bad things about Washington and the budget:

- Politicians, politicos, and advocates achieve their goals by muddying up the previous three bullet points when talking to the public. There are a select few advocates specifically concerned with the budget and a politician here and there that break this pattern.

- Politicians, politicos, and advocates who do care about the deficit care even more about how they're going to fix the deficit. This is where Evan was on to something. Democrats want to do it one way and Republicans want to do it another. The end result comes out of a political process and usually makes less sense (from a budget perspective) than either side's individual plan (although sometimes those individual plans don't make sense). Nuances like long vs. short term or macroeconomic conditions usually go completely out the window during the political process. So it's not really an issue of whether Washington cares: they do. It's an issue of what the institutions in Washington do with that.

If I were king for a day

Well, if I were king for a day I probably still wouldn't have the minimum wage at the top of my list, but let's say it was there.

People seem to impute policy views from scientific views in this discussion, so I thought I'd make this clear. If I were king for a day and had to deal with the minimum wage I would probably eliminate the federal minimum wage and let states and localities set their own if they're interested in that. Modest minimum wages might be welfare enhancing so I certainly wouldn't want to cut that policy choice off from free people. But the federal minimum wage makes very little sense, even if you think the monopsony issues are real. At some point you are going to reduce employment - monopsony is not a get out of jail free card. You hit the MRP curve eventually and after that you're in trouble. What's absolutely nuts about the federal minimum wage is that it leads to things like Alabama having a higher real minimum wage than California, and quite against Alabamans will, I might add.

This seems wrong. I don't like federalism for me but not for thee.

I think Alabama should be free to experiment with a lower minimum wage just like California has been free to experiment with that. I don't think federal fiat should prevent that.

People seem to impute policy views from scientific views in this discussion, so I thought I'd make this clear. If I were king for a day and had to deal with the minimum wage I would probably eliminate the federal minimum wage and let states and localities set their own if they're interested in that. Modest minimum wages might be welfare enhancing so I certainly wouldn't want to cut that policy choice off from free people. But the federal minimum wage makes very little sense, even if you think the monopsony issues are real. At some point you are going to reduce employment - monopsony is not a get out of jail free card. You hit the MRP curve eventually and after that you're in trouble. What's absolutely nuts about the federal minimum wage is that it leads to things like Alabama having a higher real minimum wage than California, and quite against Alabamans will, I might add.

This seems wrong. I don't like federalism for me but not for thee.

I think Alabama should be free to experiment with a lower minimum wage just like California has been free to experiment with that. I don't think federal fiat should prevent that.

Just when I thought I could liberate myself from the minimum wage discussion

A couple more points on the Murphies...

Ryan

Ryan Murphy has a good post here. I think he goes a little overboard with his first point on market socialism and Hayek. Market socialism is silly. The minimum wage is "different" because wage earnings are how people make ends meet in the modern market economy. It's the same sort of concern that got Hayek to endorse the basic income but not a "basic profit" or a "basic rent" (which has its own distortions associated with it - Hayek liked it because it met some of his ethical tests). So the center-left is not as loopy as Ryan is worried about, I think. There are good reasons here. And I suspect a lot of the center-left is like me: if we were able to design the system ourselves it would not feature a minimum wage. Remember that was one of the first safety net programs to go into effect - if we had had other better designed supports I doubt anyone would have gotten so enthusiastic about it. But it doesn't seem to be introducing all that many problems - probably because it's stayed so low - so it's certainly not going to be something I'm going to be marching on Washington for. If it stays low I could even see some welfare gains. The most appealing thing to me about discussions of the minimum wage are the scientific questions it raises, not the policy questions. Hence my initial blase reaction to the announcement. What is also getting people energized is the smearing of people like Card and Krueger as unscientific or the "no real effect" side as abandoning Econ 101.

On the second point - Ryan seems to be missing my point. I'm not proposing controlling for local price levels. I'm proposing dividing the value of the minimum wage by either a price level or a median wage or a fair market rent or something like that, because the real value of the minimum wage in Alabama is actually higher than it is in California. I got my fair market rents from here. Ryan doesn't do this - he keeps his dummy variable for the state minimum wage in there and then controls for price level. Before he goes through a lot more leg work to run it again, that's still not going to be quite right to me. You just can't look at this in the cross-section. The U.S. is a very diverse place and you at least need to look at changes in the minimum wage longitudinally to control for time-invariant state level factors. I know he's put work into it, but I have no idea what to make of it in the cross-section with a dummy variable for the minimum wage. It's certainly not going to make me budge an inch from my current assessment of Card and Krueger, Neumark and Wascher, and Dube, Lester, and Reich. If it could, these studies would all be state level cross sections with dummy variables for the minimum wage variable too.

Bob

He is concerned about correction for state-specific trends. Dube, Lester, and Reich do additional correction in their analysis for state (and region)-specific time-variant factors. This is fairly standard in the literature. I've done this in an evaluation of some child welfare reforms in Connecticut, in an evaluation of the Bush administration's High Growth Job Training Initiative, and in my analysis of the Georgia job creation tax credit which I'm preparing for submission right now. Why do people do this?

If you have only time-invariant characteristics that might affect the employment level the solution is easy: do a pre-post test. This is unrealistic which is why you never see pre-post tests.

If you have time-invariant observation-specific characteristics and time-variant characteristics common to two observations the solution is a difference-in-difference. Now it's critical here that the time-variant characteristics are common between the two observations - that's why Dube, Lester, and Reich use contiguous counties (and why Card and Krueger looked at a state border).

But even this isn't going to be perfect. Things still vary. Things always vary and our job is to hold all the variation except what we're interested in constant. Sometimes this is done by another differencing: difference in difference in differences (or DDD). For example, you might do a DID within county for adult and teenage unemployment (to clean out county-specific trends), and then do difference out the contiguous county differences (to deal with the trends common to both counties). Another strategy is to match across counties, which is useful if you've got a lot of data. This is what we did for the child welfare analysis - we did propensity score matching to control for compositional change in the child welfare case load over time that would have impacted outcomes.

Dube, Lester, and Reich - because they are working with county data - instead just choose to include state-specific and region-specific trend variables.

OK - so all of this is entirely above board. There's nothing "magical" about this as Bob's title suggests. The approach is right.

How about the execution?

Bob is suggesting that controlling for these state specific trends will over-correct because states that adopt minimum wage laws will adopt other progressive policies that we all know are just awful and will slow adult employment growth more substantially than employment growth for those earning a minimum wage.

Remember they're not just looking at people earning the minimum wage - they're looking at restaurant employment and all private employment.

Ryan Murphy, in Bob's comment thread, suggests that it's going to affect the efficiency rather than the bias of the estimate. This is basically right - collinearity should just blow up your standard errors. In this case that probably matters a little more than usual since we've got studies hovering around a zero estimate. But collinearity can actually bias the estimate if the model is misspecified. Given the trouble with identifying impacts in these sorts of policies I would err on the side of caution.

I think there's a more fundamental problem with Bob's argument. Remember, estimation is going to be off of changes in the minimum wage, not levels - that's the whole point of this exercise. In 2007 you had a bunch of conservative, right-to-work, no-state-minimum wage states increasing their minimum wage against the liberal, union-friendly, state-minimum wage states because of federal action on the matter. The same is true of every federal minimum wage increase. So if Bob thinks that these state level trends are taking too much growth off of the conservative states by attributing good policies that don't affect the minimum wage workforce to the minimum wage workforce, that would suggest that Dube, Lester, and Reich might even be underestimating the positive impact.

Ultimately I don't buy Bob's argument because my impression is that regional growth trends that have nothing to do with the liberalism or conservatism of the state probably dominate these state-specific trends. The South was conservative when it was growing really slow too, after all. The Midwest and the Northeast had a lot of unions in their period of strong growth. I just don't buy the argument.

But it's not a bad argument under certain circumstances. If he's right that liberal policies matter that much (and in the direction he thinks they matter) this would be something to worry about if it were the liberal states increasing their minimum wage. But in a lot (at least as many? more? I don't know) of cases since it's the federal minimum wage that's increases it's actually conservative states that are doing the increasing.

Ryan

Ryan Murphy has a good post here. I think he goes a little overboard with his first point on market socialism and Hayek. Market socialism is silly. The minimum wage is "different" because wage earnings are how people make ends meet in the modern market economy. It's the same sort of concern that got Hayek to endorse the basic income but not a "basic profit" or a "basic rent" (which has its own distortions associated with it - Hayek liked it because it met some of his ethical tests). So the center-left is not as loopy as Ryan is worried about, I think. There are good reasons here. And I suspect a lot of the center-left is like me: if we were able to design the system ourselves it would not feature a minimum wage. Remember that was one of the first safety net programs to go into effect - if we had had other better designed supports I doubt anyone would have gotten so enthusiastic about it. But it doesn't seem to be introducing all that many problems - probably because it's stayed so low - so it's certainly not going to be something I'm going to be marching on Washington for. If it stays low I could even see some welfare gains. The most appealing thing to me about discussions of the minimum wage are the scientific questions it raises, not the policy questions. Hence my initial blase reaction to the announcement. What is also getting people energized is the smearing of people like Card and Krueger as unscientific or the "no real effect" side as abandoning Econ 101.

On the second point - Ryan seems to be missing my point. I'm not proposing controlling for local price levels. I'm proposing dividing the value of the minimum wage by either a price level or a median wage or a fair market rent or something like that, because the real value of the minimum wage in Alabama is actually higher than it is in California. I got my fair market rents from here. Ryan doesn't do this - he keeps his dummy variable for the state minimum wage in there and then controls for price level. Before he goes through a lot more leg work to run it again, that's still not going to be quite right to me. You just can't look at this in the cross-section. The U.S. is a very diverse place and you at least need to look at changes in the minimum wage longitudinally to control for time-invariant state level factors. I know he's put work into it, but I have no idea what to make of it in the cross-section with a dummy variable for the minimum wage. It's certainly not going to make me budge an inch from my current assessment of Card and Krueger, Neumark and Wascher, and Dube, Lester, and Reich. If it could, these studies would all be state level cross sections with dummy variables for the minimum wage variable too.

Bob

He is concerned about correction for state-specific trends. Dube, Lester, and Reich do additional correction in their analysis for state (and region)-specific time-variant factors. This is fairly standard in the literature. I've done this in an evaluation of some child welfare reforms in Connecticut, in an evaluation of the Bush administration's High Growth Job Training Initiative, and in my analysis of the Georgia job creation tax credit which I'm preparing for submission right now. Why do people do this?

If you have only time-invariant characteristics that might affect the employment level the solution is easy: do a pre-post test. This is unrealistic which is why you never see pre-post tests.

If you have time-invariant observation-specific characteristics and time-variant characteristics common to two observations the solution is a difference-in-difference. Now it's critical here that the time-variant characteristics are common between the two observations - that's why Dube, Lester, and Reich use contiguous counties (and why Card and Krueger looked at a state border).

But even this isn't going to be perfect. Things still vary. Things always vary and our job is to hold all the variation except what we're interested in constant. Sometimes this is done by another differencing: difference in difference in differences (or DDD). For example, you might do a DID within county for adult and teenage unemployment (to clean out county-specific trends), and then do difference out the contiguous county differences (to deal with the trends common to both counties). Another strategy is to match across counties, which is useful if you've got a lot of data. This is what we did for the child welfare analysis - we did propensity score matching to control for compositional change in the child welfare case load over time that would have impacted outcomes.

Dube, Lester, and Reich - because they are working with county data - instead just choose to include state-specific and region-specific trend variables.

OK - so all of this is entirely above board. There's nothing "magical" about this as Bob's title suggests. The approach is right.

How about the execution?

Bob is suggesting that controlling for these state specific trends will over-correct because states that adopt minimum wage laws will adopt other progressive policies that we all know are just awful and will slow adult employment growth more substantially than employment growth for those earning a minimum wage.

Remember they're not just looking at people earning the minimum wage - they're looking at restaurant employment and all private employment.

Ryan Murphy, in Bob's comment thread, suggests that it's going to affect the efficiency rather than the bias of the estimate. This is basically right - collinearity should just blow up your standard errors. In this case that probably matters a little more than usual since we've got studies hovering around a zero estimate. But collinearity can actually bias the estimate if the model is misspecified. Given the trouble with identifying impacts in these sorts of policies I would err on the side of caution.

I think there's a more fundamental problem with Bob's argument. Remember, estimation is going to be off of changes in the minimum wage, not levels - that's the whole point of this exercise. In 2007 you had a bunch of conservative, right-to-work, no-state-minimum wage states increasing their minimum wage against the liberal, union-friendly, state-minimum wage states because of federal action on the matter. The same is true of every federal minimum wage increase. So if Bob thinks that these state level trends are taking too much growth off of the conservative states by attributing good policies that don't affect the minimum wage workforce to the minimum wage workforce, that would suggest that Dube, Lester, and Reich might even be underestimating the positive impact.

Ultimately I don't buy Bob's argument because my impression is that regional growth trends that have nothing to do with the liberalism or conservatism of the state probably dominate these state-specific trends. The South was conservative when it was growing really slow too, after all. The Midwest and the Northeast had a lot of unions in their period of strong growth. I just don't buy the argument.

But it's not a bad argument under certain circumstances. If he's right that liberal policies matter that much (and in the direction he thinks they matter) this would be something to worry about if it were the liberal states increasing their minimum wage. But in a lot (at least as many? more? I don't know) of cases since it's the federal minimum wage that's increases it's actually conservative states that are doing the increasing.

Saturday, February 23, 2013

A data note, for people just getting into empirical reserch

It's always good to know things like who is captured in certain surveys, the difference between household and individual surveys, standard definitions of things like "unemployment" or "income", etc. - just little things to know your way around data.

For student readers/people just getting into empirical research - I've run into another common one recently that's worth noting too: industrial and occupational categories change over time, so keep an eye on that. You don't need to memorize all the different classifications, but just know that it comes up. I lost a third of the IT workforce this morning from January 2010 to January 2012. The recession was bad but not that bad. I had a suspicion and sure enough a new occupational code went into effect in the interim. Most things don't change in this sort of recoding but if something that you're looking at changes it can make a big difference.

A second case - in revising the engineering chapter about two weeks ago I was adding a table on the industry that different engineering fields work in in 1980 and 2010, to look at any changes. There was one big change for marine engineers from Manufacturing (I was using big industrial sectors and very detailed occupational sectors) to Transportation.

A major change in the work of marine engineers?

Nope.

Turns out a handful of very detailed industries completely switched sectors over that thirty years. Specifically, shipbuilding taking place in drydocks was moved from Manufacturing to Transportation, while shipbuilding not taking place in drydocks stayed in Manufacturing.

Not a big deal for the most part - but when you're looking at marine engineers and half them do shipbuilding in drydocks and half do shipbuilding not in drydocks, it can make for some big swings in employment!

For student readers/people just getting into empirical research - I've run into another common one recently that's worth noting too: industrial and occupational categories change over time, so keep an eye on that. You don't need to memorize all the different classifications, but just know that it comes up. I lost a third of the IT workforce this morning from January 2010 to January 2012. The recession was bad but not that bad. I had a suspicion and sure enough a new occupational code went into effect in the interim. Most things don't change in this sort of recoding but if something that you're looking at changes it can make a big difference.

A second case - in revising the engineering chapter about two weeks ago I was adding a table on the industry that different engineering fields work in in 1980 and 2010, to look at any changes. There was one big change for marine engineers from Manufacturing (I was using big industrial sectors and very detailed occupational sectors) to Transportation.

A major change in the work of marine engineers?

Nope.

Turns out a handful of very detailed industries completely switched sectors over that thirty years. Specifically, shipbuilding taking place in drydocks was moved from Manufacturing to Transportation, while shipbuilding not taking place in drydocks stayed in Manufacturing.

Not a big deal for the most part - but when you're looking at marine engineers and half them do shipbuilding in drydocks and half do shipbuilding not in drydocks, it can make for some big swings in employment!

A fifty year retrospective on the Moynihan report

Two and a half hours of reflection by a lot of great people here. I haven't gotten a chance to listen to it yet.

Here's the participant list:

• Gregory Acs, director, Income and Benefits Policy Center, Urban Institute

• Michelle Alexander, author, The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness

• Kenneth Braswell, executive director, Fathers Incorporated

• Ronald Mincy, director, Center for Research on Fathers, Children and Family Well-Being, Columbia University

• Helen Mitchell, director, strategic planning & policy development, Office of U.S. Representative Danny Davis

• Janks Morton, producer, What Black Men Think

• Jeffrey Shears, director, Social Work Research Consortium, Department of Social Work, University of North Carolina—Charlotte

• Margaret Simms, director, Low-Income Working Families project, Urban Institute

Here's the participant list:

• Gregory Acs, director, Income and Benefits Policy Center, Urban Institute

• Michelle Alexander, author, The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness

• Kenneth Braswell, executive director, Fathers Incorporated

• Ronald Mincy, director, Center for Research on Fathers, Children and Family Well-Being, Columbia University

• Helen Mitchell, director, strategic planning & policy development, Office of U.S. Representative Danny Davis

• Janks Morton, producer, What Black Men Think

• Jeffrey Shears, director, Social Work Research Consortium, Department of Social Work, University of North Carolina—Charlotte

• Margaret Simms, director, Low-Income Working Families project, Urban Institute

PhD labor market

So far I have not delved specifically into the PhD labor market in my work on S&E and high skill labor markets. As many of you are probably aware, it is a completely different world. Many of the same issues apply: lagged labor market adjustmet, prospects of a glut if demand shifts, specialized labor, likely externalities, etc. If you are interested in this labor market specifically, you'll want to read Ronald Ehrenberg, Paula Stephan, and Richard Freeman.

But there is an interesting series of blog posts on this labor market I wanted to bring attention to by Jordan Weissmann here and here. My co-author on a lot of this work, Hal Salzman, was talking with Weissmann in preparation for these posts and he told me he gets the impression more will be coming.

But there is an interesting series of blog posts on this labor market I wanted to bring attention to by Jordan Weissmann here and here. My co-author on a lot of this work, Hal Salzman, was talking with Weissmann in preparation for these posts and he told me he gets the impression more will be coming.

Education premiums and disadvantaged groups

A lot of you have probably been hearing about this new study by Dwyer, Hodson, and McCloud suggesting that women earn higher returns to education than men, which is part of the reason that men are more likely to drop out (Greg Mankiw highlights a piece of it here).

This is similar to my findings with Marla McDaniel in our Review of Black Political Economy article on the impact of a high school diploma on employment for youth who did not go on to college (so a completely different segment of the labor market from this work on college). The two big takeaway from the paper were that black high school graduates had comparable employment profiles to white high school dropouts (I had a similar conclusion using a different dataset in this recent briefing paper). But the other notable finding was that although black graduates do worse, the added benefit of graduating is greater than for whites.

It wasn't one of those awesome deal-with-the-endogeneity papers but it had a lot of things that you don't normally have like mental health scores, cognitive ability scores, measures of the quality of home life, etc. Kitchen sink regressions aren't great, but when you start getting at that kind of stuff I feel like the results are more robust. If anything it's an underestimate I'd expect because obviously these students aren't going to the same quality schools.

So this phenomenon seems to be popping up a lot. Why?

One answer is a catch-up-growth kind of convergence story that you could borrow from macro, but I doubt that's a major role since abilities are fairly well controlled for.

I think the answer probably has to do with differential statistical discrimination in the labor market, as laid out in this excellent paper on racial disparities in unemployment by Ritter and Taylor, which really guided a lot of my thinking in writing up the RBPE paper. White workers - particularly young ones without much work history - have an easier time signalling their productivity to white employers than minorities (the same would go for women signalling their productivity to male employers). Statistical discrimination is never a complete strategy in the hiring process but it's likely to be more heavily relied upon when hiring minority workers. So you can think of getting a degree either as jumping to a higher distribution where employers are still using statistical discrimination, or as the higher tail of the distribution getting a better signal out about their productivity. Education doesn't matter as much for white or male workers because more of their signal was already picked out from the noise.

This is similar to my findings with Marla McDaniel in our Review of Black Political Economy article on the impact of a high school diploma on employment for youth who did not go on to college (so a completely different segment of the labor market from this work on college). The two big takeaway from the paper were that black high school graduates had comparable employment profiles to white high school dropouts (I had a similar conclusion using a different dataset in this recent briefing paper). But the other notable finding was that although black graduates do worse, the added benefit of graduating is greater than for whites.

It wasn't one of those awesome deal-with-the-endogeneity papers but it had a lot of things that you don't normally have like mental health scores, cognitive ability scores, measures of the quality of home life, etc. Kitchen sink regressions aren't great, but when you start getting at that kind of stuff I feel like the results are more robust. If anything it's an underestimate I'd expect because obviously these students aren't going to the same quality schools.

So this phenomenon seems to be popping up a lot. Why?

One answer is a catch-up-growth kind of convergence story that you could borrow from macro, but I doubt that's a major role since abilities are fairly well controlled for.

I think the answer probably has to do with differential statistical discrimination in the labor market, as laid out in this excellent paper on racial disparities in unemployment by Ritter and Taylor, which really guided a lot of my thinking in writing up the RBPE paper. White workers - particularly young ones without much work history - have an easier time signalling their productivity to white employers than minorities (the same would go for women signalling their productivity to male employers). Statistical discrimination is never a complete strategy in the hiring process but it's likely to be more heavily relied upon when hiring minority workers. So you can think of getting a degree either as jumping to a higher distribution where employers are still using statistical discrimination, or as the higher tail of the distribution getting a better signal out about their productivity. Education doesn't matter as much for white or male workers because more of their signal was already picked out from the noise.

Friday, February 22, 2013

Did Don Boudreaux - for a second time in as many days - propose a shift in the MRP curve as a counter-argument for a shift along the MC curve?

Here.

I think he is again, but someone please confirm my intuition.

If you make someone take a break for a quarter of every hour they are working on the job you are roughly reducing their productivity by a quarter. You are shifting the MRP curve to the left. That will give you a new equilibrium where you are going to have lower employment and lower wages.

The same goes for a tax on wages that government imposes on the firm (his initial counter-argument).

Neither of these are at all comparable to the shift along the MC curve that a minimum wage is alleged to accomplish.

Another way of putting it is this: nothing about taxing the firm prevents it from exercising the exact same monopsony power - setting quantity such that MC=MRP and the wage as low as it goes. They just do that with a new MRP curve. Nothing about deliberately making workers less productive (presumably in a way that those workers would like) prevents the firm from exercising the exact same monopsony power - setting quantity such that MC=MRP and the wage as low as it goes. Again, they just do that with a new MRP curve.

Setting a minimum wage does prevent them from exercising monopsony power and as long as it is modest enough it will present them with a wage bargain that would be found mutually beneficial. Should we look at other margins of exploitation? Ya, sure. But that's a different issue.

I feel like I'm taking crazy pills here. Am I? What am I missing about these arguments?

I think he is again, but someone please confirm my intuition.

If you make someone take a break for a quarter of every hour they are working on the job you are roughly reducing their productivity by a quarter. You are shifting the MRP curve to the left. That will give you a new equilibrium where you are going to have lower employment and lower wages.

The same goes for a tax on wages that government imposes on the firm (his initial counter-argument).

Neither of these are at all comparable to the shift along the MC curve that a minimum wage is alleged to accomplish.

Another way of putting it is this: nothing about taxing the firm prevents it from exercising the exact same monopsony power - setting quantity such that MC=MRP and the wage as low as it goes. They just do that with a new MRP curve. Nothing about deliberately making workers less productive (presumably in a way that those workers would like) prevents the firm from exercising the exact same monopsony power - setting quantity such that MC=MRP and the wage as low as it goes. Again, they just do that with a new MRP curve.

Setting a minimum wage does prevent them from exercising monopsony power and as long as it is modest enough it will present them with a wage bargain that would be found mutually beneficial. Should we look at other margins of exploitation? Ya, sure. But that's a different issue.

I feel like I'm taking crazy pills here. Am I? What am I missing about these arguments?

Thursday, February 21, 2013

Heckman on early childhood education

Here.

Heckman is a very talented, very technical economist who has made crucial contributions to the science. He's one of those guys that I worry people will fail to appreciate if they get told about "over-mathematized economics" or "mainline vs. mainstream" or whatever you want to call it.

Heckman is a highly technical writer who non-technical, non-economists have appreciated. At the Urban Institute his work on early childhood was considered essential by the developmental psychologists and child welfare experts with an interest in policy.

Heckman is a very talented, very technical economist who has made crucial contributions to the science. He's one of those guys that I worry people will fail to appreciate if they get told about "over-mathematized economics" or "mainline vs. mainstream" or whatever you want to call it.

Heckman is a highly technical writer who non-technical, non-economists have appreciated. At the Urban Institute his work on early childhood was considered essential by the developmental psychologists and child welfare experts with an interest in policy.

A note on specific Austrians

Bob Murphy has come under a lot of heat for his inflation predictions. Probably rightly so so long as the nature of that heat is appropriate. He should think through why we didn't see prices go up and indeed he has thought through that.

Murphy is associated with the Mises Institute which is often associated with the "bad/crazy Austrians". And indeed, there are some crazy ones down there in Auburn.

But Bob Murphy has never given me the impression that he doubts that I accept Smithian principles of spontaneous order through a market process. He also thinks OLG models are important and flexible tools for thinking through problems - he doesn't yearn for some literary economic golden age, nor does he harass mathematical economists as somehow being averse to good literary exposition.

You never have to play those bullshit games with him.

You basically toss around the arguments and the data. You recognize models are just tools for thinking.

Bob does get caught up in Krugman, of course. But he's usually trying to catch him in a contradiction, not argue that he's some kind of monster. His Rothbardianism can be tough for some people to take. You have to learn to co-exist with arguments that preventing a civilization killing asteroid is unethical or just close comments when you're thinking out loud about war.

But all in all, he's a good sort of Austrian - not that he's always right but that he's an Austrian you can usually work through an argument with.

So - just because the heat has been on him and there's this presumption that Fairfax is civilized and Auburn is barbaric - I thought that was worth saying.

Murphy is associated with the Mises Institute which is often associated with the "bad/crazy Austrians". And indeed, there are some crazy ones down there in Auburn.

But Bob Murphy has never given me the impression that he doubts that I accept Smithian principles of spontaneous order through a market process. He also thinks OLG models are important and flexible tools for thinking through problems - he doesn't yearn for some literary economic golden age, nor does he harass mathematical economists as somehow being averse to good literary exposition.

You never have to play those bullshit games with him.

You basically toss around the arguments and the data. You recognize models are just tools for thinking.

Bob does get caught up in Krugman, of course. But he's usually trying to catch him in a contradiction, not argue that he's some kind of monster. His Rothbardianism can be tough for some people to take. You have to learn to co-exist with arguments that preventing a civilization killing asteroid is unethical or just close comments when you're thinking out loud about war.

But all in all, he's a good sort of Austrian - not that he's always right but that he's an Austrian you can usually work through an argument with.

So - just because the heat has been on him and there's this presumption that Fairfax is civilized and Auburn is barbaric - I thought that was worth saying.

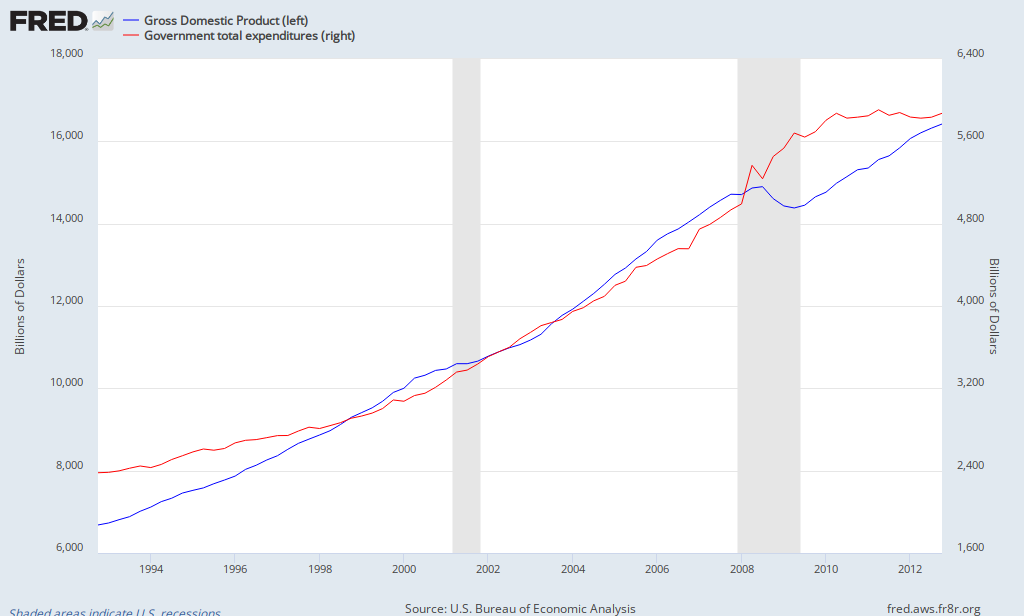

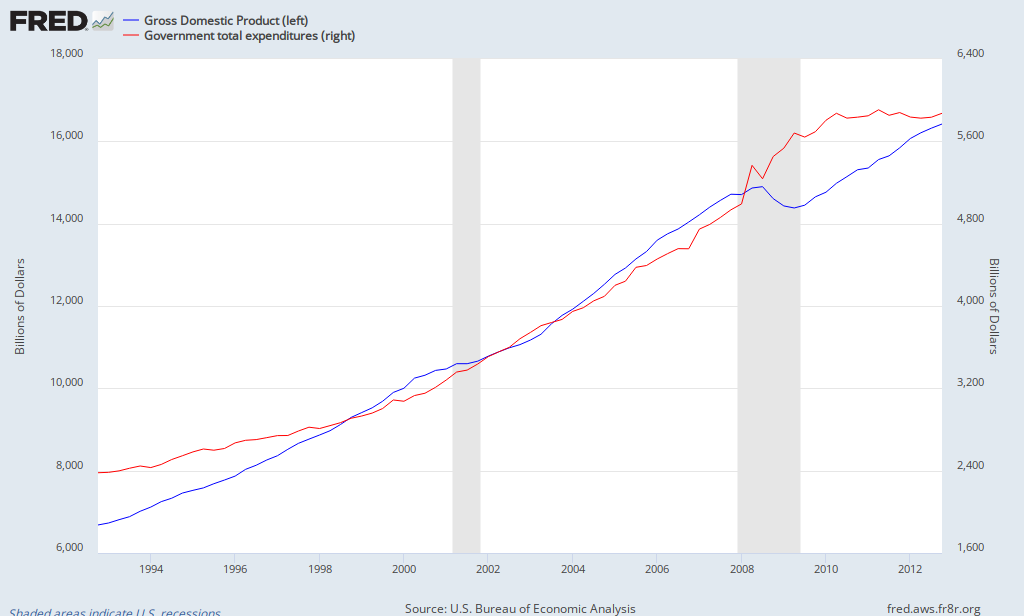

Graph of the day - for sequester pondering

Blue is NGDP, red is nominal government expenditures. Scales are different.

I do not understand how people can actually treat what is effectively a permanent cut in spending (same pound of flesh every year for the next ten years) as fiscal responsibility in this environment.

Budget baselines are very frustrating things to deal with, but one thing should be clear: some kind of baseline is important to have. People like Paul Gregory (HT - Russ Roberts) are remarking on the fact that discretionary spending is still projected to increase $110 billion over the next decade despite the approximately trillion dollar cuts.

If someone told you NGDP was going to increase by over a trillion but in fact it's only going to increase by $110 billion would you say "no big deal - it's still growing!". No - you'd call that a depression.

For my younger readers I'm sure you're expecting real earnings growth throughout your career. You're not going to be earning your current salary forever. Think of your anticipated salary growth ten years from now. Now if you actually got only 10 percent of that growth, would you consider that a good thing? How would your plans change?

NGDP is badly off trend but it is growing (although last quarter was ominous). Government expenditure is effectively flat-lined.

If any other component of output did this people would recognize it for the problem that it is. If this were your salary you would recognize it for what it is. But when it's "other people's money", stupidity reigns.

Note that government expenditures don't have the persistent trend line that NGDP does. We can fiddle with it - I'm not saying that's off the table. Ironically the spending protected from the sequester (entitlements and direct war spending) is exactly where we have our spending problems that ought to be addressed. But the idea that now is the time to do it or this is the way to do it is ridiculous.

I do not understand how people can actually treat what is effectively a permanent cut in spending (same pound of flesh every year for the next ten years) as fiscal responsibility in this environment.

Budget baselines are very frustrating things to deal with, but one thing should be clear: some kind of baseline is important to have. People like Paul Gregory (HT - Russ Roberts) are remarking on the fact that discretionary spending is still projected to increase $110 billion over the next decade despite the approximately trillion dollar cuts.

If someone told you NGDP was going to increase by over a trillion but in fact it's only going to increase by $110 billion would you say "no big deal - it's still growing!". No - you'd call that a depression.

For my younger readers I'm sure you're expecting real earnings growth throughout your career. You're not going to be earning your current salary forever. Think of your anticipated salary growth ten years from now. Now if you actually got only 10 percent of that growth, would you consider that a good thing? How would your plans change?

NGDP is badly off trend but it is growing (although last quarter was ominous). Government expenditure is effectively flat-lined.

If any other component of output did this people would recognize it for the problem that it is. If this were your salary you would recognize it for what it is. But when it's "other people's money", stupidity reigns.

Note that government expenditures don't have the persistent trend line that NGDP does. We can fiddle with it - I'm not saying that's off the table. Ironically the spending protected from the sequester (entitlements and direct war spending) is exactly where we have our spending problems that ought to be addressed. But the idea that now is the time to do it or this is the way to do it is ridiculous.

On Austrian economics - a mix of productive thoughts and unproductive navel gazing - if that doesn't interest you don't complain to me in the comments - I'm warning you now

Here's Krugman and DeLong.

I find Austrian economics interesting from a history of thought perspective and due to their prominence in current debates (thanks in large part to the internet). I also find Cantillon effects interesting, probably real, but not particularly important (and probably theorized a little backwards - a point a forthcoming paper of mine should make clear). Other than that I don't think there's much of anything useful in Austrian economics that isn't also in mainstream economics. You can say it's nice that they care about uncertainty or knowledge or that they think socialism can't work. That stuff's wonderful, but doesn't offer a compelling reason to declare oneself an Austrian. This isn't to say you can't get something out of reading Austrians. There's lots of great stuff to get out of reading Austrians. It's just to say that it makes a better literature than it does a modern school of thought. I think people who like to think of themselves as Austrians would be better off just thinking of themselves as economists that like to read Austrian literature (he might disagree with me on this, but I think of Ryan Murphy in much this way - hell, that's me to a certain extent).

So in that sense I feel like I'm not as dismissive of Austrian economics as Krugman and DeLong are, but obviously I still tick off a lot of Austrians...

...but I can see what motivates Krugman and DeLong.

Krugman is pretty much considered a monster by Austrians. There are Austrian blogs dedicated to criticizing him. Those not so designated have him as a regular feature. Peter Boettke wrote this of Krugman when he won his well-deserved Nobel: "the Swedes just made perhaps the worst decision in the history of the prize today in naming Paul Krugman the 2008 award winner...today I would say is a sad day for economics, not a day to be celebrated. Mises supposedly said during his dying days that he hoped for another Hayek, as I am picking up my jaw from the floor I am hoping for another Samuelson or Arrow to get the award rather the hackonomics that was just honored."

Steve Horwitz leaps from Krugman thinking WWII got us out of the Depression to: "In Krugman’s version of Orwell’s Newspeak, destruction creates wealth, and war, though not ideal, is morally acceptable because it produces economic growth... To argue as Krugman does is to abandon both economics and morality. Big Brother would be proud."

We are regularly told not to judge Austrian economics by the crazy "internet Austrians" - so I'm careful here to select people that are considered the upstanding citizens.

Of course, it's precisely things like this that create the crazier "internet Austrians".

It is not a very easy bunch to talk with.

It's in precisely this environment of a flame-war over Krugman that Krugman remarks on the tendencies of this small group of economists and hangers-on that appears to be obsessed with him. That's not particularly outlandish IMO. If Krugman called Boettke's work "hackonomics", I think it would be fair for Boettke to strike at the character of his accuser. As far as I know Krugman's never said that of Boettke. This would also be the case if Krugman said Horwitz abandoned morality and that Big Brother would be proud of him.

The volume of the attacks on Krugman dwarf the response. We can pretty much count Krugman's forays into Austrian economics on our hands: the Slate piece, the discussion of the sushi model, Murphy's inflation prediction, Krugman having the gall to not appreciate Hoppe saying he should be spoken to like a child, this one from yesterday, etc... In contrast, you cannot go for a single day without a big-name Austrian mentioning Krugman disparagingly. And when Krugman does respond it's more often of the "your ideas seem utterly wrong and fringe" not of the "you're a warmonger" variety.

So while I completely agree and am happy to say that Krugman doesn't really appreciate the depth and breadth of the Austrian position, I find it very hard to point the finger at him on this sort of thing.

I also want to call attention to this particularly excellent insight by Krugman about Austrian economics: "Its devotees believe that they have access to a truth that generations of mainstream economists have somehow failed to discern"

I don't know if Austrians really understand how infuriating this is or how stupid it makes them appear. When people already think that order in human society is spontaneous and not planned, when they already see politics without romance, when they already think that capital and labor are heterogeneous, when they agree that relative prices drive behavior - getting told day after day after day that they don't think these things and they ought to forces them to either conclude (1.) the accusers don't know what they're talking about, or (2.) it's not worth talking to the accusers any more.

This accusation is very hard for "reasonable" Austrians to run from. It's one of hte major theses of Peter Boettke's new book, which has been widely celebrated.

I, like Krugman, consider the recent growth in Austrian economics to bring some real costs with it for society and for the profession (I probably see a few more benefits than Krugman does). Since I apparently have something of an audience I've found it worth confronting these views that (to use Krugman's phrase) "they have access to a truth that generations of mainstream economists have somehow failed to discern". As efforts like John Papola's and movements like the Tea Party bring more people in that seems even more important to me to address. But lately I have been leaning more heavily toward the second option: it's not worth talking to the accusers any more.

I've had lots of people email me or comment on the blog and let me know that they've dropped Austrian economics and that my blog played a role in that. That is encouraging. Good economics matters to me - that's what all this here and all my effort professionally is all about. It's not so much that Austrian economics is "bad economics" - that list of truths that Austrians think they have special access to that I had above is good economics. It's that there's also a lot of bad economics and bad faith and a willingness to dismiss good science that pervades that community.

But I don't know how many are really going to be convinced, and there are many other things I could be doing. I was thinking the other day about Boettke's mainline/mainstream distinction. I could write a whole paper on how the greatest producers of Smithian economics today are Arrow, Romer, Krugman (for the major themes of the invisible hand, growth, and trade), and Stiglitz (for the scraps - efficiency wages, credit rationing, asymmetric information, monopoly power - all originally major arguments of Smith). It would be a very strong argument. But the people that would care are - I fear - unmovable, and the rest won't care. I'd be much better off writing about the S&E labor market or expanding my work on hiring credits to the North and South Carolina programs or time use decisions in the household.

Both paths are good economics, economics I'm excited about, and questions that are important. But the latter set is distinctive in that people seem to appreciate the contribution. When I tell people in the S&E workforce community that I and people who think like me think that it's important to understand the role of the market process in the S&E workforce, they've pretty much accepted that. When I tell people in the Austrian community that I and people who think like me consider it important to understand the role of the market process in generating a flourishing society, they often refuse to take "yes" for an answer and insist on explaining it to me. That gets old, and I have to confess it sometimes makes me wonder how much substance is really there to engage.

I find Austrian economics interesting from a history of thought perspective and due to their prominence in current debates (thanks in large part to the internet). I also find Cantillon effects interesting, probably real, but not particularly important (and probably theorized a little backwards - a point a forthcoming paper of mine should make clear). Other than that I don't think there's much of anything useful in Austrian economics that isn't also in mainstream economics. You can say it's nice that they care about uncertainty or knowledge or that they think socialism can't work. That stuff's wonderful, but doesn't offer a compelling reason to declare oneself an Austrian. This isn't to say you can't get something out of reading Austrians. There's lots of great stuff to get out of reading Austrians. It's just to say that it makes a better literature than it does a modern school of thought. I think people who like to think of themselves as Austrians would be better off just thinking of themselves as economists that like to read Austrian literature (he might disagree with me on this, but I think of Ryan Murphy in much this way - hell, that's me to a certain extent).

So in that sense I feel like I'm not as dismissive of Austrian economics as Krugman and DeLong are, but obviously I still tick off a lot of Austrians...

*****

...but I can see what motivates Krugman and DeLong.

Krugman is pretty much considered a monster by Austrians. There are Austrian blogs dedicated to criticizing him. Those not so designated have him as a regular feature. Peter Boettke wrote this of Krugman when he won his well-deserved Nobel: "the Swedes just made perhaps the worst decision in the history of the prize today in naming Paul Krugman the 2008 award winner...today I would say is a sad day for economics, not a day to be celebrated. Mises supposedly said during his dying days that he hoped for another Hayek, as I am picking up my jaw from the floor I am hoping for another Samuelson or Arrow to get the award rather the hackonomics that was just honored."

Steve Horwitz leaps from Krugman thinking WWII got us out of the Depression to: "In Krugman’s version of Orwell’s Newspeak, destruction creates wealth, and war, though not ideal, is morally acceptable because it produces economic growth... To argue as Krugman does is to abandon both economics and morality. Big Brother would be proud."

We are regularly told not to judge Austrian economics by the crazy "internet Austrians" - so I'm careful here to select people that are considered the upstanding citizens.

Of course, it's precisely things like this that create the crazier "internet Austrians".

It is not a very easy bunch to talk with.

It's in precisely this environment of a flame-war over Krugman that Krugman remarks on the tendencies of this small group of economists and hangers-on that appears to be obsessed with him. That's not particularly outlandish IMO. If Krugman called Boettke's work "hackonomics", I think it would be fair for Boettke to strike at the character of his accuser. As far as I know Krugman's never said that of Boettke. This would also be the case if Krugman said Horwitz abandoned morality and that Big Brother would be proud of him.

The volume of the attacks on Krugman dwarf the response. We can pretty much count Krugman's forays into Austrian economics on our hands: the Slate piece, the discussion of the sushi model, Murphy's inflation prediction, Krugman having the gall to not appreciate Hoppe saying he should be spoken to like a child, this one from yesterday, etc... In contrast, you cannot go for a single day without a big-name Austrian mentioning Krugman disparagingly. And when Krugman does respond it's more often of the "your ideas seem utterly wrong and fringe" not of the "you're a warmonger" variety.

So while I completely agree and am happy to say that Krugman doesn't really appreciate the depth and breadth of the Austrian position, I find it very hard to point the finger at him on this sort of thing.

*****

I also want to call attention to this particularly excellent insight by Krugman about Austrian economics: "Its devotees believe that they have access to a truth that generations of mainstream economists have somehow failed to discern"

I don't know if Austrians really understand how infuriating this is or how stupid it makes them appear. When people already think that order in human society is spontaneous and not planned, when they already see politics without romance, when they already think that capital and labor are heterogeneous, when they agree that relative prices drive behavior - getting told day after day after day that they don't think these things and they ought to forces them to either conclude (1.) the accusers don't know what they're talking about, or (2.) it's not worth talking to the accusers any more.

This accusation is very hard for "reasonable" Austrians to run from. It's one of hte major theses of Peter Boettke's new book, which has been widely celebrated.